Decisions happening behind closed doors due to a lack of transparency of the scientific evidence has been a notable concern about the UK’s response to Covid-19. [1] The last of the BBC daily briefings was held on 24 June 2020. During these a Minister regularly stood in the middle of two senior members of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). The job of SAGE is to pool together scientific experts and provide scientific advice to the Cabinet Office Briefing Room (COBR). Although decisions are made by the Government’s Ministers, not SAGE, the phrase ‘we are following the science’ was regularly used to justify decisions during these briefings.

Former Government Chief Scientific Advisor, Sir David King, established a separate group of experts called Independent SAGE in reaction to and part of this growing push for transparency. He warned the secrecy of the response could cause a loss of public trust in the science.[2] Independent SAGE’s first meeting was on the 4 May 2020 and live streamed on YouTube. Their website is an obvious ‘dig’ at the Ministers’ rhetoric as it uses the tagline ‘Independent SAGE. Following the Science’. [3]

Sir David King, Chair of Independent SAGE. Image source: Climaterepair via Wikimeida

Independent SAGE’s quest for transparency has not stopped since their inception. The latest change being live weekly meetings with their own scientific experts on their social media channels as a response to the end of the Government’s daily briefings, with the first of these being held on 26 June 2020. There are now over 10 meetings that the public can view on Independent SAGE’s YouTube channel. [4] Several reports and open letters are also available on Independent SAGE’s website. Topics include (but are not limited to) school openings, test and trace options and the impact of Covid-19 on Black and Minority Ethnic populations.

This blog post uses media coverage to better understand these notions of transparency, the differences between SAGE and Independent SAGE and how SAGE has changed in the context of transparency over the duration of the pandemic. These sections consider whether a new standard of transparency has been set for SAGE but also highlights potential issues of having more than one scientific advisory group (albeit one not official) and the limitations of their outreach.

The origins of Independent SAGE and ongoing calls for transparency

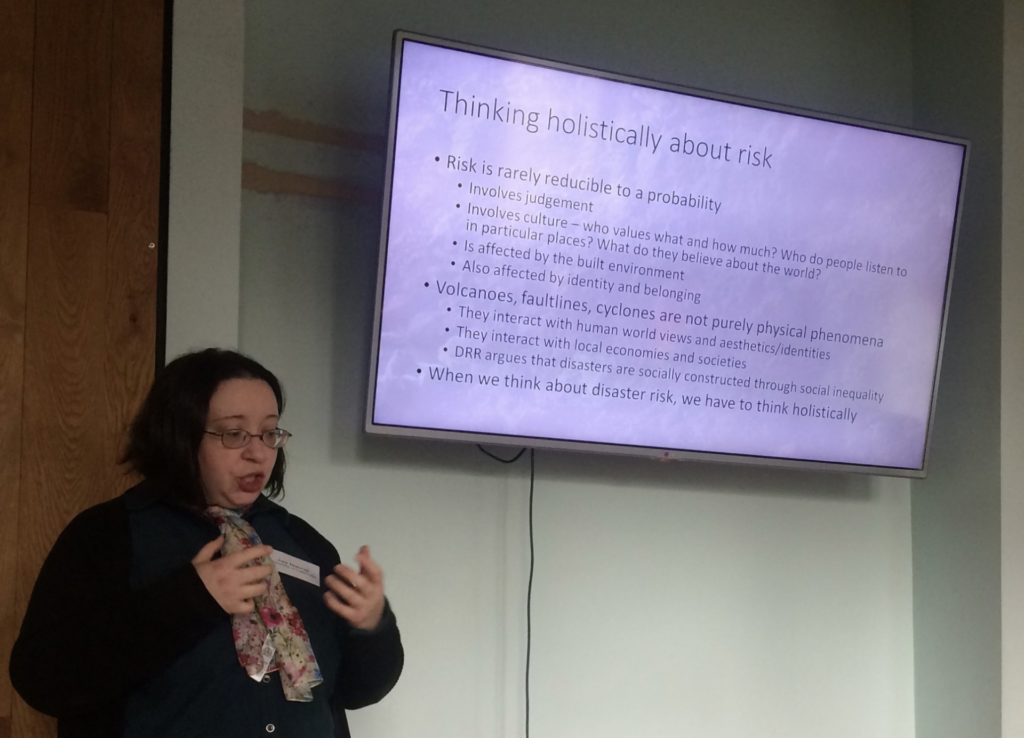

As soon as UK’s ministers claimed to follow the science, calls for transparency of the scientific evidence started gaining traction. As commented by James Wilsdon, a digital science professor of research policy at Sheffield University: ‘transparency must now become the default operating mode across the SAGE process…We’re in a situation of what some call ‘post-normal’ science, where the facts are uncertain, values are in dispute, stakes are high and decisions are urgent’ (4 May).[5]

Although these calls for transparency were circulating since the beginning of the pandemic, a notable push to know the experts’ names came after a Guardian article on 24 April revealed that two political figures Dominic Cummings and Ben Warner had attended SAGE meetings. [6] Despite Downing Street reporting they did not participate, there was uneasiness in the media that the scientific advice was being politicised before it went up to COBR.[7] Consequently, ‘concern over the secretary of SAGE’s membership reached a new pitch’. [8] Shortly after this, Independent SAGE was established. However, in his recent interview with The Times, Sir David King indicates that ‘the seeds of Independent SAGE began to germinate’ in February when he had noticed the divergence of the UK’s approach to the rest of the world and the WHO’s advice to ‘test, test, test’. [9]

As part of their quest for transparency, Independent SAGE wanted to distinguish between the science and the politics. On 22 May, news broke in the Mirror and Guardian accusing Dominic Cummings of breaking lockdown rules. Despite a press conference in the rose garden of 10 Downing Street to explain his movements, there was an explosion of media coverage, including calls for his resignation. [10] Whether or not he broke the lockdown rules, articles emerged critiquing scientists for standing alongside ministers as they justified his decisions. The one article in The Guardian claimed the relationship between scientists and ministers had become ‘dangerously collusive’.[11]

In Independent SAGE’s meeting on 28 May the panel was asked ‘Why do you think the Government is ignoring its own advice and why [have] Whitty and Vallance in particular stopped appearing?’. Although not explicitly mentioning Dominic Cummings, it is highly likely the ongoing media coverage of him in the previous week underpinned the question. Susan Michie, Professor of Health Psychology at UCL responded: “One thing I think that is very important going forward is that scientific trust isn’t dented at all… it would be extremely helpful if our chief medical advisor and chief scientific officer were to give direct press briefings and direct briefings to the public to report on the scientific thinking of SAGE.” [12]: 47:20 – 48.17mins.

Independent SAGE’s online discussions take the format that Susan Michie referred to: no ministers, just scientists. In some cases, a reporter may help facilitate the discussion by welcoming members of the public to ask a question or asking one on their behalf. The most appropriate expert is then chosen to answer and others may raise their hand to indicate they also have something to add. In some cases, the public’s questions are included in the report Independent SAGE send to the Government. An example being Section 7 in their report about schools: ‘School reopening: some of your questions answered’. [13]

If watching the live Independent SAGE’s discussion on YouTube, you can see the public’s comments. Some offering opinions about the topic being discussed, but the ones that stood out for me (obviously due my interest in transparency) are those thanking Independent SAGE for indeed that, their transparency, openness and honesty. On 27 June a Crowdfunding page was set up for Independent SAGE to continue their work. The comments here also provide interesting reading. For example, one states: ‘I donated because ISAGE are working for open/transparent and effective policies to deal with COVID19. I thank them all for working on behalf of all’. [14]

Since the setup of Independent SAGE, Sir David King and other members of Independent SAGE have become increasingly visible scrutinising the decisions that the Government has made. In one of his latest interviews (published 27 June), Sir David King comments that if members of SAGE were as visible “it would have changed this immensely”. He then reiterates the critique of the ongoing rhetoric mentioned earlier: “you can’t have a minister or prime minister saying we’re just following the science advice if the public doesn’t know what the science advice was”. [9]

Although Independent SAGE’s visibility has increased since their establishment and they are being referred to in more media headlines, there are limitations to their outreach and communication of the latest scientific thinking. Those aware of Independent SAGE are likely to be those actively seeking the discussion about the scientific evidence. At the time of writing (14 July 2020), Independent SAGE have 57.8k Twitter followers and 10.9k YouTube subscribers. [15, 16] The co-chairs of the official SAGE, Professor Chris Whitty and Sir Patrick Vallance (England’s Chief Medical Officer and the UK’s Chief Scientific Advisor) have their own Twitter pages with 256.9K and 137.6K followers respectively, SAGE itself does not have a page. [17, 18] On the face of it, these numbers sound quite large. However political figures such as Boris Johnson and Donald Trump have 2.9M and 83.4M respectively, whilst to take an extreme example, celebrities such as Justin Bieber have 112.2M. [19 ,20, 21] Compared to these numbers, the outreach of Independent SAGE is small.

Nonetheless, Independent SAGE was only established a few months ago and the 57.8K followers indicates there is a significant interest in them. Independent SAGE do not claim to be a communication platform for the guidelines but a platform for informed discussions which can be accessed by people if they so desire.

How is Independent SAGE different to SAGE?

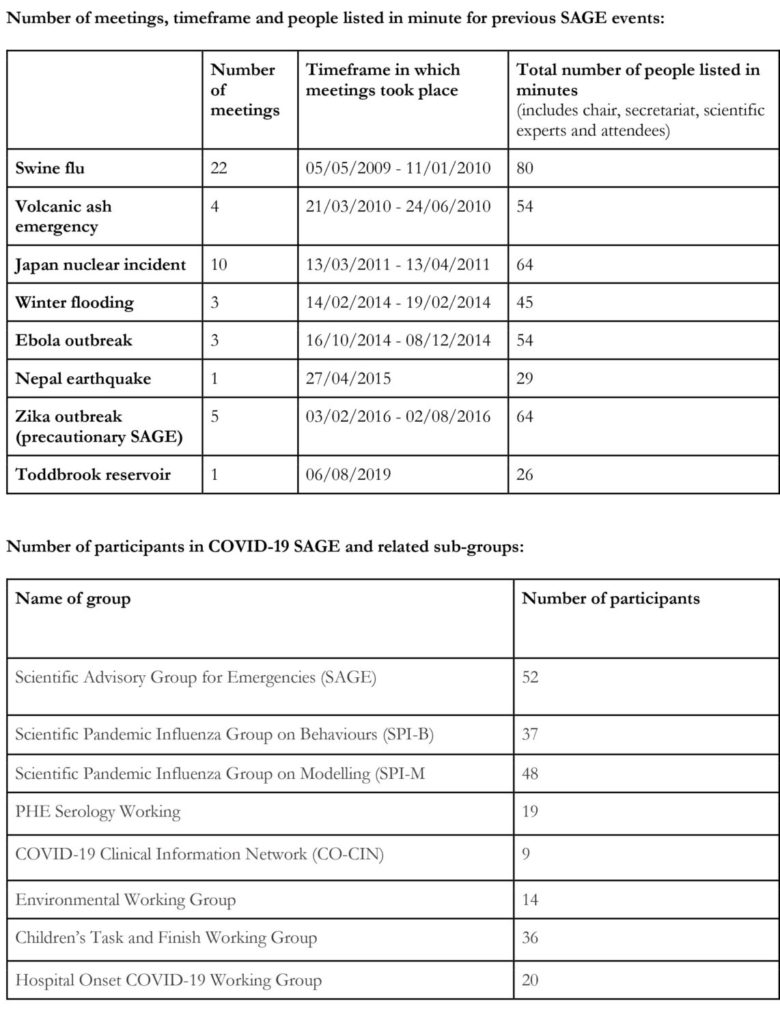

Independent SAGE and SAGE are both made up of a body of experts from different disciplines. The official SAGE has 55 members listed as well as several sub-groups which focus on behavioural science, disease modelling, serology (scientific study or diagnostic examination of blood serum), clinical information, environmental modelling, transmission in children and hospital onset. [22] Independent SAGE originally comprised of the Chair, Sir David King, and 12 members. This has since been expanded to include a Behavioural Science Advisory Group, composed of 9 members. Some members of Independent SAGE or its sub-groups are part of SAGE or its sub-groups but the two bodies are different as Independent SAGE’s reports do not form part of the official government response.[3]

The two groups have been mixed up on more than one occasion. During news broadcasts, members of Independent SAGE (who are not also on SAGE) have accidently been referred to as members of the official SAGE by reporters and they have had to correct them. Another more specific example of this mix up happened on the 22 May when the deputy Labour Minister, Angela Rayner, accidently referred to SAGE after Independent SAGE had published a report advising against the reopening of schools on 1 June: ‘SAGE concludes June 1st “too soon” to open schools. Teacher unions have been absolutely correct in asking for safety measures to be in place before re-opening’.[23] She later tried to clarify that she meant Independent SAGE but subsequently both Tweets were deleted after she was accused of spreading misinformation.[24] Her statement has been fact checked on the website ‘full fact’.[23]

In contrast to the two bodies being mixed up, several headlines have referred to Independent SAGE as a ‘rival’ group of experts.[25, 26, 27, 28] In response to the use of the terminology ‘rivals’, Sir David King Tweeted ‘some have billed @IndependentSAGE as a ‘rival’ to the govts. To be absolutely clear that is not how we as a group see ourselves. Science is best when our community works together, on IndiSAGE we have a broad church of experts who are working hard to supplement existing advice’ (23 May).[29]

The mix-up and perception of Independent SAGE as ‘rivals’ emphasises a potential problem with having two separate bodies. If they are seen to contradict one another, does that just add to confusion? Should there be just the one clear voice? Or is that simply the notion of science, there is not always consensus and that’s what is important for the public to see and understand? In another interview, Sir David King explains that scientists do not always agree and science is a discipline based on the peer review process where the evidence can be scrutinised, hence the objective of Independent SAGE is to offer this scrutiny and that is why it is vital that the science being referred to by decision makers is available.[8]

A noticeable difference between SAGE and Independent SAGE is the visibility and direct communication with the experts in the public sphere. The public did have access to senior members of SAGE, such as Sir Patrick Vallance and Professor Chris Whitty during the daily briefings where a few questions were posed by the public. However, beyond this, as far as I’m aware, there haven’t been any conversations between just the scientists that are open to the general public to listen to and participate. This is the vision of Independent SAGE. As expressed by Karl Friston, a neuroscientist advising Independent SAGE: “I think of Independent Sage as the ultimate exercise in public engagement; what it would look like if you and I and everyone else were able to sit in on a real Sage meeting… In my view there can never be anything wrong with transparent, informed discussion.” [30]

Ascribing the virtue of public engagement to Independent SAGE should be carefully considered. In town planning policy, the terminology of public participation has many levels, from the consultation being tokenistic to the public having a significant impact on the design of a development. The channel that Independent SAGE has opened informs the public through a question and answer session, where some of those concerns are passed onto the government. They do not give access to the inner workings of writing the report. Nonetheless, access to a more in-depth question and answer session is an important quality and Whitty himself has noted that he has been much more shorthanded than he would have liked in the briefings when he was questioned about the changing guidelines of social distancing from 2m to 1m+ in the last daily briefing. [31]: 40.46 – 41.00mins.

There is a practical feasibility issue in having meetings like Independent SAGE, especially as the official SAGE includes more experts and sub-groups and all of those members will be under significant time-pressures (that’s not to say members of Independent SAGE are not busy as they are also volunteering their time whilst being in full time work). However, if some of the experts in the official SAGE, beyond those in senior roles, were able to factor in an hour of their time to answer some of the public’s concerns directly and in the format of a group discussion, it would be welcomed by members of the public seeking more detail about the scientific evidence. This question and answer format would help to balance the concerns about protecting national security and being open with the public as the public wouldn’t be listening into the actual deliberations but could still hear directly, and in more detail about what the science unpinning decisions is. Navigating through the evidence on the website for SAGE can quite easily become overwhelming.

Another difference between SAGE and Independent SAGE is the perception that Independent SAGE is a left-wing body. An example of this is the Daily Mail headline: ‘Ex-science tsar Sir David King has built a Left-wing cabel to disperse virus health advice (but says ministers’ experts are too political to be trusted!’.[32] In response to this criticism, Sir David King once again used Twitter as the communication channel and stated that political ideology is irrelevant and that the job of the scientific experts is to give scientific advice not political advice, and emphasised that it is up to the ministers to make the decisions.[33] The very fact that he had to respond, shows that the perception is/was there, so much so he felt it needed addressing.

The ‘boundary’ between science and politics has been an issue throughout the pandemic. How has the science been used within decisions which are inevitably political? Hence, the calls for transparency and concerns about trust. Scientists who are/were members of SAGE, such as Professor John Edmunds and Professor Neil Ferguson, have separately spoken out that lockdown did not happen soon enough and was being eased too quickly, whilst Melanie Smallman, a Lecturer in Science and Technology Studies at UCL, describes the terminology ‘Independent SAGE’ as an oxymoron arguing that that ‘the idea that government advisers can separate science and politics is bogus’. [34, 35, 36]

Has SAGE’s approach to transparency changed during the pandemic?

A short and simple answer to this question is yes. At the beginning of the pandemic, none of the evidence being referred to was available, the expert’s names were not released and the minutes of the meetings were not accessible. When there were the growing calls to release the names of the experts, Sir Patrick Vallance said the decision to not release them was due to concerns about safeguarding the individual’s personal security, based on advice from Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure.[37] However, pressure continued to mount and the experts were given an opt-out option and then the names were released on the 4 May. This was the same day as Independent SAGE’s first meeting, which Sir David King has commented he doesn’t think was a coincidence.[38]

The Government Office for Science’s website for SAGE openly acknowledges that SAGE’s approach has changed during the course of the pandemic. The website says that in previous events the minutes and supporting documentation were not published until the conclusion of the relevant emergency in order to protect any national security and operational considerations and allow ministers to consider ‘free and frank advice’ from the experts. It also states ‘we have revisited this approach in light of the current exceptional circumstances, recognising the high level of public interest in the nature and content of SAGE advice’.[39] Then it goes on to say, SAGE will now publish all past minutes and supporting documents and future minutes and documentations within one month of the meeting taking place. To overcome the concerns about protecting individuals and national security, in some cases information is redacted from these. When following the link to the minutes, the website user is taken to a page with the header ‘Transparency and freedom of information releases’ specific to SAGE. [40] In a comment in The Telegraph, Sir Patrick Vallance also acknowledges this change in SAGE saying ‘when it comes to this crisis it is clear we must get the information out as soon as possible, and in my opinion, as close to real time as is feasible and compatible with allowing ministers the time they need’. [41]

Obviously, the current approach is more transparent than it was at the start of the pandemic but as we are in such a fast-moving situation, to some, a one-month delay in the publication is not satisfactory, particularly for those that want to review and scrutinise the evidence before decisions are made, rather than just be informed what the evidence is when there are key policy changes. An example of evidence being released as policy changed is after an announcement on 23 June. In this announcement the public were told that from 4 July, the 2m social distancing rule could be reduced to 1m+ if social distancing was not possible. The + meaning with mitigation measures. A review of the 2 metre social distancing guidance was published by the Cabinet Office on the 24 June. [42] Within the text of this, a link is provided to a SAGE report from a meeting on the 4 June (published 12 June) entitled ‘Transmission of SARS-CoV2 and Mitigating Measures’.[43] In this, the executive summary states ‘Physical distancing is an important mitigation measure (high confidence). Where a situation means that 2m face-to-face distancing cannot be achieved it is strongly recommended that additional mitigation measures including (but not limited to) face coverings and minimising duration of exposure are adopted (medium confidence)’.

In addition to the release of experts’ names and evidence, scientists have emphasised that SAGE’s job is to advise, not make decisions. A document published on 5 May explaining what SAGE is and its response to Covid-19 outlines that ‘The government is not beholden to what SAGE says, and the evidence SAGE puts forward forms just one part of what the government considers before adopting new policies and interventions during an emergency. In this current pandemic, the government also has to consider other factors’.[44] Another example being, Sir Patrick Vallance describing what SAGE is and how the science is being used for decisions in his comment in The Telegraph on 30 May. He acknowledges that SAGE is not a group of people in consensus, that the science will not always be right and that it will change over time as we learn more. He also noted that science advice is just that, advice and the ‘Ministers must decide and have to take many other factors into consideration’.[41] In the last daily briefing, Professor Chris Whitty made it clear that decisions on the easing of lockdown are a balance of risk. These are risks accepted by the Ministers to reduce the spread of the virus but also open up the economy. They are also risks accepted by individuals as they go about their everyday life. In order for individuals to make informed decisions, the pressure remains for the emerging scientific evidence to become available.

It’s very easy to criticise in situations where you are not the decision maker, or even one of the main advisers, Sir David King himself says he’s glad he’s not currently in Sir Patrick Vallance’s position.[9] However, it’s clear that if Ministers say they are ‘following the science’, they should recognise that many people want to know what this science is. Without that, trust can easily be lost. If trust is lost, this can impact whether or not people follow the guidelines. Although it will be impossible to pinpoint exactly what caused SAGE to make the changes that it did, such as the release of experts’ names, evidence and minutes, undoubtedly the fact this is an event affecting everyone’s daily life led to the growing calls for transparency. Independent SAGE have clearly made their point about what they think this transparency should look like. It is likely the group contributed to the growing pressure, particularly with their presence on Twitter, which then fed into members being contacted by news outlets and several articles referring to ‘Independent SAGE’s’ advice, particularly when that went against the latest government decisions.

An open letter to the leaders of the UK political parties published in the British Medical Journal was published on 24 June following the last daily briefing expressing concern over the preparedness for a second wave.[45] If there is a little ‘breathing room’ over the summer months, one part of this preparedness should be reflecting on the communication of the science and the evidence. SAGE should continue to release the minutes and update the evidence, but perhaps this could be taken a step further by applying some of the principles of Independent SAGE including hosting online discussions with only scientific experts and not ministers, as well as a more active presence on Twitter and other social media platforms to direct people towards these updates. Even if there is not a second wave, there will be future events that SAGE will be involved in and now there is this increased awareness of them, they will inevitable be under increased scrutiny – so the notion of transparency needs to continue wherever feasibly possible.

However, it is important to note that one limitation of this blog post is that it has assumed transparency is a good virtue which should be strived towards. Before the pandemic (2017), Dr Stephen John, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Cambridge, argues that transparency is not always beneficial. One reason being, transparency can increase confusion as members of the public may expect consensus and that’s not what science always is.[46] In the context of Covid-19 we have seen that if the evidence is not released, it gives the impression that the Government are hiding information from the public, however if released the public can pick and choose what they communicate on social media or to their peers. In the last few days, we have seen lots of mixed messages about face coverings, the Metro’s headline (13 July) being: ‘Call to clear up the mask muddle’.[47] As the evidence for face coverings has changed over time, people arguing for and against them, are selecting the evidence which supports their viewpoint. If we assume transparency is a good virtue due to the provision of information for those that seek it, these problems of mixed messaging and misinformation need to be overcome. The Government need to carefully consider the communication channels that they use and how to extend their outreach. This communication needs to clearly explain what the guidelines are but also, as with the face mask debate, why they have changed. Clarity is key.

Text by Dr Hannah Baker

Disclaimer: Published 14 July 2020. This article is based on media coverage and reports found online. Despite her best efforts to locate all relevant information, the author acknowledges there may be key pieces of information she would have missed. Members of Independent SAGE or SAGE have not been contacted for comment.

Thumbnail image source: Climaterepair via Wikimeida

References:

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/world/europe/uk-coronavirus-sage-secret.html

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/03/publics-trust-in-science-at-risk-warns-former-no-10-adviser

[3] https://www.independentsage.org/who-is-on-the-independent-sage/

[4] https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCqqwC56XTP8F9zeEUCOttPQ

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2020/may/04/no-10-facing-fresh-calls-for-transparency-over-sage-pandemic-advice

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/24/revealed-dominic-cummings-on-secret-scientific-advisory-group-for-covid-19

[7] https://theconversation.com/dominic-cummings-and-sage-advisory-groups-veil-of-secrecy-has-to-be-lifted-137228

[8] https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-uk-politics-2020-5-new-covid-19-science-advice-group-launched-to-rival-sage/

[9] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/sir-david-king-where-the-uk-has-gone-wrong-on-covid-19-and-what-we-should-do-now-nvhdxf7p9

[10] https://www.itv.com/news/2020-05-25/timeline-how-the-dominic-cummings-controversy-unfolded/

[13] https://www.independentsage.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Independent-Sage-Brief-Report-on-Schools.pdf

[14] https://www.gofundme.com/f/indepdent-sage

[15] https://twitter.com/IndependentSage

[16] https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCqqwC56XTP8F9zeEUCOttPQ

[17] https://twitter.com/CMO_England

[18] https://twitter.com/uksciencechief

[19] https://twitter.com/BorisJohnson

[20] https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump

[21] https://twitter.com/justinbieber

[22] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/scientific-advisory-group-for-emergencies-sage-coronavirus-covid-19-response-membership/list-of-participants-of-sage-and-related-sub-groups

[23] https://fullfact.org/health/sage-did-not-advise-against-reopening-schools-1-june/

[24] https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/angela-rayner-s-sage-fake-news

[25] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/05/05/three-scientific-unknowns-could-change-course-life-outside-lockdown/

[26] https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/politics/rival-coronavirus-science-advisors-urge-21973564

[27] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/04/rival-sage-group-covid-19-policy-clarified-david-king

[28] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8281751/Former-chief-scientific-adviser-sets-rival-Sage.html?ito=amp_twitter_share-top

[29] https://twitter.com/Sir_David_King/status/1264105252233654272

[30] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/31/covid-19-expert-karl-friston-germany-may-have-more-immunological-dark-matter

[31] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdakYCF1hXc

[32] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8286797/GUY-ADAMS-Ex-science-tsar-Sir-David-King-told-switch-diesel.html

[33] https://twitter.com/Sir_David_King/status/1260557481715142656

[34] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52849691

[35] https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/198155/neil-ferguson-talks-modelling-lockdown-scientific/

[36] https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-political-science-blog-2020-5-independent-sage-group-is-an-oxymoron/

[35] https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/science-and-technology/david-king-independent-sage-coronavirus-covid-19-government-transparency

[37] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5801/cmselect/cmsctech/correspondence/Patrick-Vallance-to-Greg-Clark-re-SAGE-composition.pdf

[38] https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-news-uk-politics-2020-5-independent-sage-group-is-making-government-more-open/

[39] https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/scientific-advisory-group-for-emergencies-sage-coronavirus-covid-19-response

[40] https://www.gov.uk/search/transparency-and-freedom-of-information-releases?organisations%5B%5D=scientific-advisory-group-for-emergencies&parent=scientific-advisory-group-for-emergencies

[41] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/05/30/will-have-learned-lot-including-do-better-next-time-science/

[42] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-two-metre-social-distancing-guidance

[43] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/892043/S0484_Transmission_of_SARS-CoV-2_and_Mitigating_Measures.pdf

[44] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/883104/sage-explainer-5-may-2020.pdf

[45] https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m2514

[46] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02691728.2017.1410864

[47] https://www.metro.news/calls-to-clear-up-the-mask-muddle/2076904/