The Universal, the Individual, and the Novel: Hegel, Austen, and Ethical Formation

February 22, 2019 at 10 a.m.

Robertson Gymnasium 1000A

The seminar will focus on Professor Lewis’s recent piece “The Universal, the Individual, and the Novel: Hegel, Austen, and Ethical Formation,” which itself constitutes work toward a larger book project. While much recent work in ethics has focused on a purported absence in modern ethical thought of practices for the formation of good character, that book will argue that practices of ethical formation have neither gone away nor ceased to be objects of concern. They have migrated to the margins in canonical modern thought; but even in the case of canonical modern thinkers, scrutiny reveals much more attention to practices of ethical formation than scholars typically appreciate. In the wake of the Reformation, these practices have largely become embedded in ordinary life. Accordingly, four sites have taken on particular significance: home, school, work, and church. Lewis’s project seeks to uncover and argue for the significance of oft-neglected treatments of ethical formation from a decisive moment in Western thought. In providing a more nuanced account of the history of modern ethics, he seeks to demonstrate what we can learn from these debates about the compatibility of a distinctly modern emphasis on freedom and close attention to the formation of character.

Reading

“The Universal, the Individual and the Novel: Hegel, Austen and Ethical Formation,” in The Unique, the Singular and the Individual, ed. Ingolf U. Dalferth (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, Forthcoming).

Recommended

G.W.F. Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right, §§ 142-160 and §§ 257-270.

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park

Essays by Professor Lewis available via email upon request:

“Feeling, Representation, and Practice in Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion.” In The Oxford Handbook of Hegel, ed. Dean Moyar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 581-602.

“Beyond Love: Hegel on the Limits of Love in Modern Society.” Zeitschrift für neuere Theologiegeschichte/Journal for the History of Modern Theology 20:1 (2013): 3-20.

“Cultivating Our Intuitions: Hegel on Religion, Politics, and Public Discourse,” in Religion, Modernity, and Politics in Hegel (OUP, 2011).

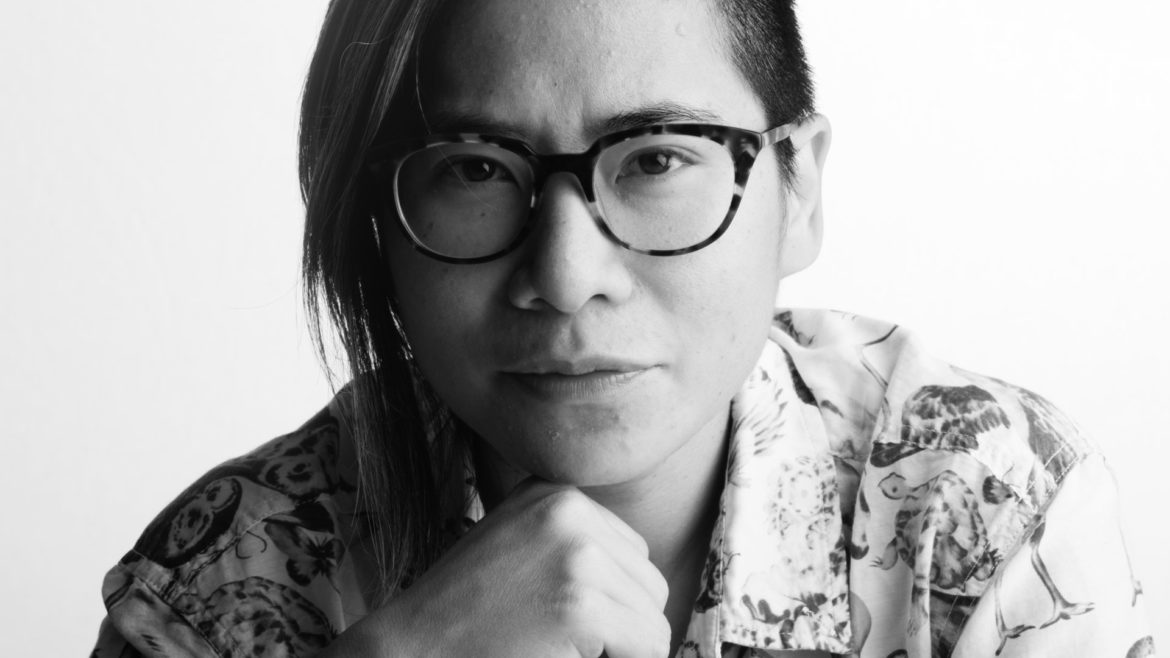

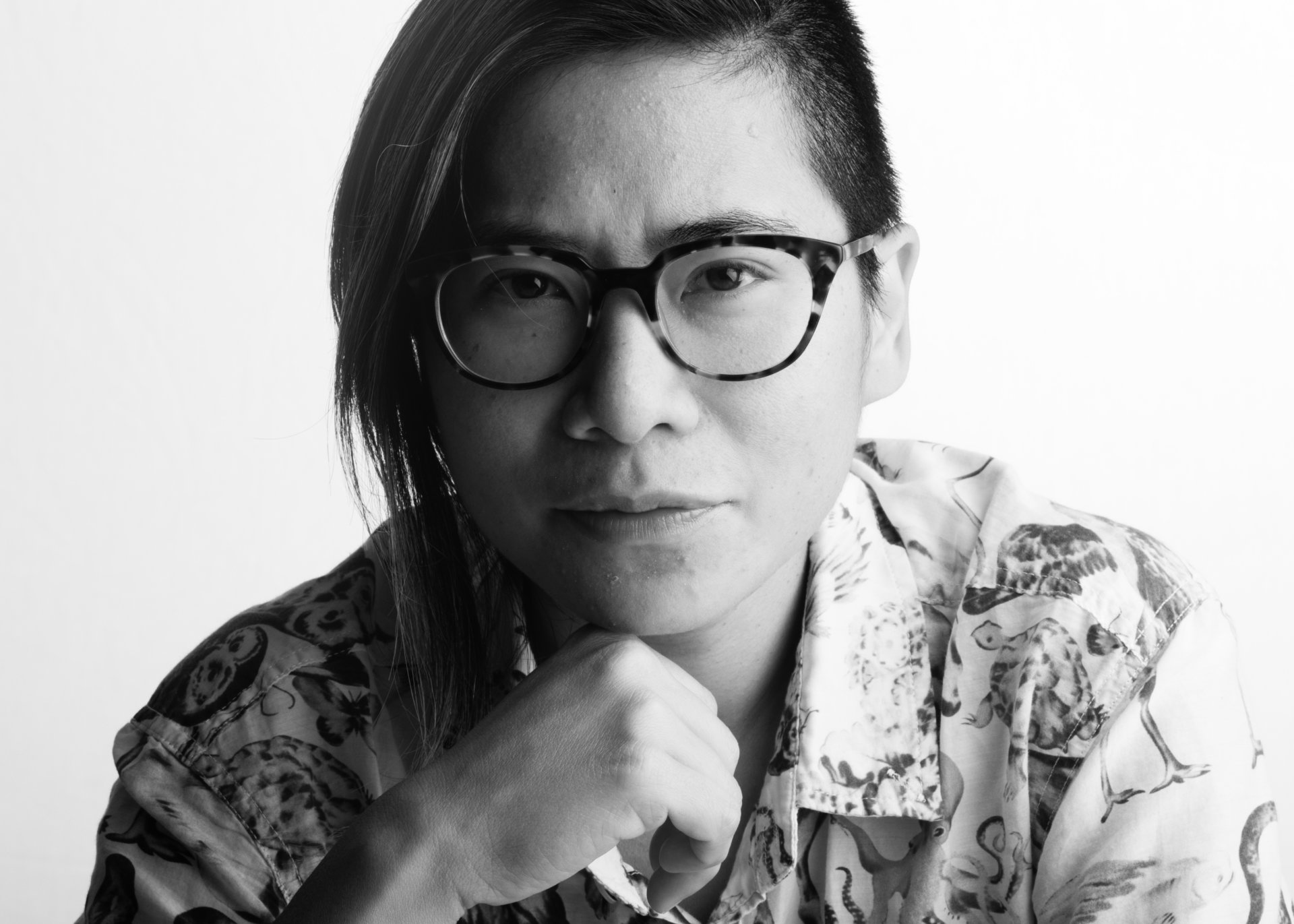

Thomas A. Lewis is Professor of Religious Studies, as well as Co-Deputy Dean and Associate Dean of Academic Affairs in the Graduate School, at Brown University. He has taught previously at the University of Iowa and at Harvard University. He specializes in religious ethics and philosophy of religion in the modern West and has strong interests in methodology in the study of religion. His research examines conceptions of tradition, reason, and authority and their significance for ethical and political thought. His publications include Freedom and Tradition in Hegel: Reconsidering Anthropology, Ethics, and Religion (University of Notre Dame Press, 2005); Religion, Modernity, and Politics in Hegel (Oxford University Press, 2011); Why Philosophy Matters for the Study of Religion–and Vice Versa (Oxford University Press, 2015); and articles on religion and politics, liberation theology, communitarianism, and comparative ethics.