Regions and Cities: Policy Narratives and Policy Challenges in the UK

by Philipp McCann

Many of the narratives that now dominate policy debates in the United Kingdom and Europe regarding questions of interregional convergence and divergence are derived from observations overwhelmingly based on the experience of the United States, and to a much smaller extent Canada and Australia (Sandbu 2020). These narratives often focus on the supposed ‘Triumph of the City’ (Glaeser 2011) and the problems of ‘left behind’ small towns and rural areas. Moreover, many debates about ‘the city’ – which immediately jump to discussions of London, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Paris, Tokyo, etc. – often have very little relevance for thinking about how the vast majority of urban dwellers live and work, in most parts of the world.

Unfortunately, however, the empirical evidence suggests that many of these narratives only have very limited applicability to the European context (Dijkstra et al. 2015). The European context is a patchwork of quite differing national experiences, and these types of US-borrowed narratives only reflect the urban and rural growth experiences of a few western European countries such as France, plus the central European former-transition economies (Dijkstra et al. 2013; McCann 2015).

Interregional divergence has indeed been a feature of most countries since the 2008 crisis and this is also likely to increase in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis, but not necessarily in the way that these US narratives suggest. Indeed, it is important to consider these issues in detail because interregional inequality has deep and pernicious social consequences (Collier 2018), without necessarily playing any positive role in economic growth. Across the industrialised world there is no relationship between national economic growth and interregional inequality (Carrascal-Incera et al. 2020), and more centralised states tend to be more interregionally unequal and to have much larger primal cities. In the case of the UK, very high interregional inequality and an over-dominance by London has been achieved with no national growth advantage whatsoever over competitor countries.

The problems associated with narrative-transfer leading to policy-transfer are greatly magnified in the UK due to our poor language skills, whereby UK media, think-tanks, ministries and media are only really able to benchmark the UK experience against the experiences of other English-speaking countries such as USA, Canada and Australia. Yet, when it comes to urban and regional issues this particular grouping of countries in reality represents just about the least applicable comparator grouping possible. These countries are each larger than the whole of Europe, they have highly polycentric national spatial structures, and they are federal countries, whereas the UK is smaller than Wyoming, is almost entirely monocentric, and is an ultra-centralised top-down unitary state with levels of local government autonomy akin to Albania or Moldova (OECD 2019).

These problems are now evident again in the UK in the debates regarding ‘levelling up’. When we think about the role of cities and regions in our national growth story, in the case of the UK it is very difficult to translate many of the ideas currently popular in the North American urban economics arena to the specifics of the UK context. The literature on agglomeration economies and also the widespread international empirical evidence confirms that cities are key drivers of national economic growth, and evidence from certain countries suggests that nowadays there are large and growing productivity differences between urban and rural regions.

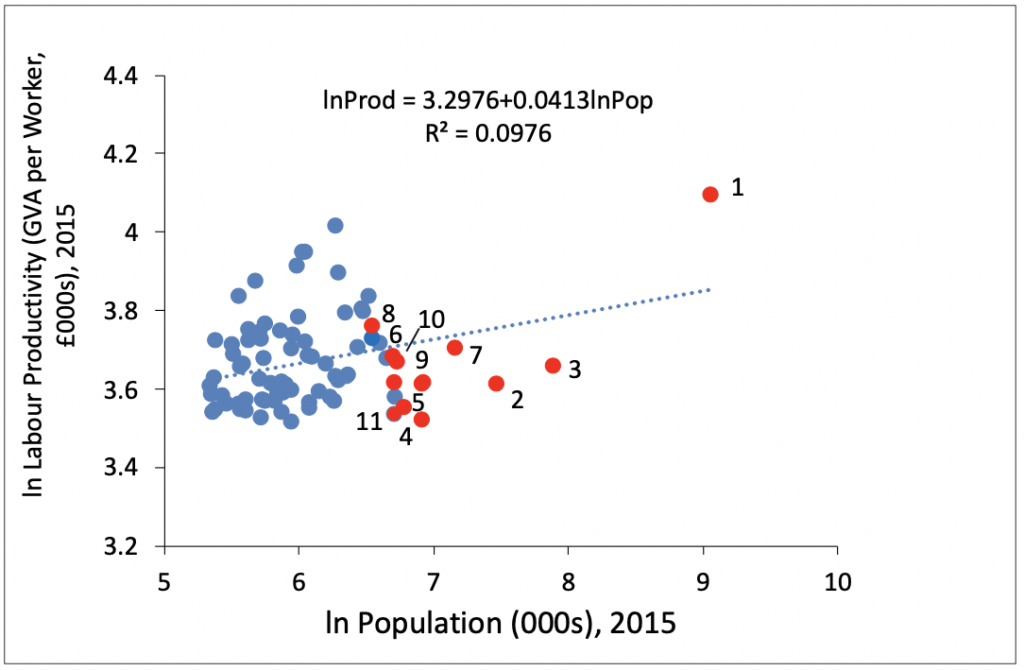

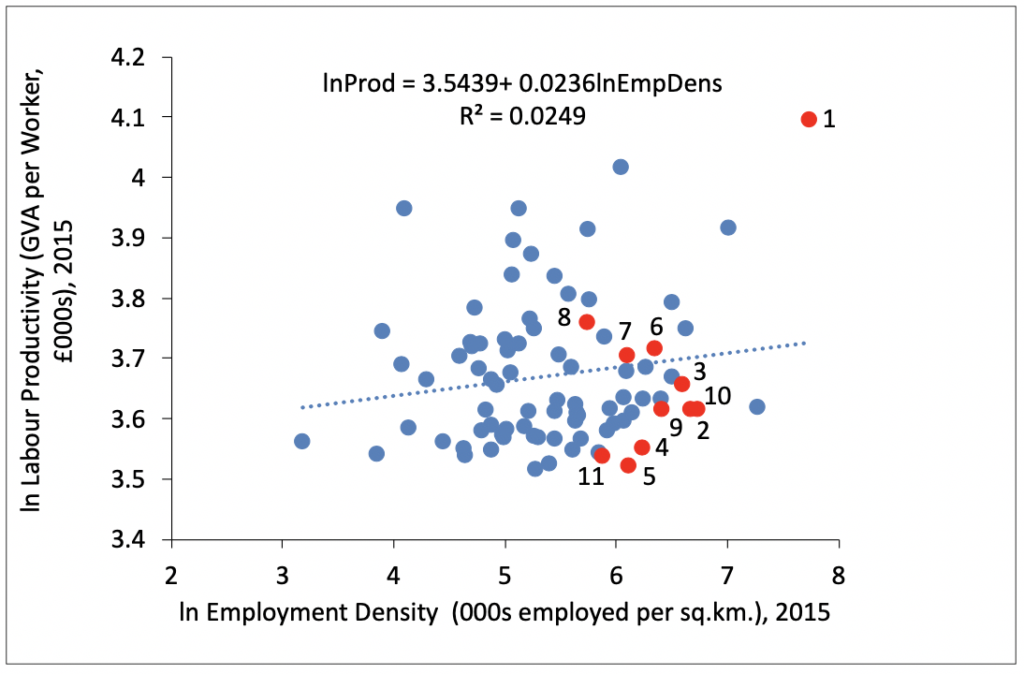

Yet, in the UK case the evidence suggests that these patterns are only partially correct. Some very prosperous urban areas such as London, Edinburgh, Oxford, Bristol, Reading and Milton Keynes contribute heavily to the national economic growth story. On the other hand, many of the UK’s large cities located outside of the South of England underperform by both national and international standards and contribute much less to economic performance than might otherwise be expected on the basis of international comparators (McCann 2016).

What are the features of this under-performance? Firstly, in the UK there is almost no relationship between localised productivity and the size of the urban area (Ahrend et al. 2015; OECD 2015), especially once London is removed from the analysis, whereas positive city size-productivity relationships are widely observed in many countries. Secondly, there are only very small productivity differences between the performance of large cities and urban areas, between small cities and towns, and between urban areas in general and rural areas (ONS 2017). Indeed, many of the UK’s most prosperous places are small towns and rural areas while some of the poorest places in the UK are large cities. Thirdly, sectoral explanations play an ever-decreasing role (Martin et al. 2018) and interregional migration has remained largely unchanged for four decades (McCann 2016). Fourthly, a simple and mechanistic reading of Zipf’s Law tells us little or nothing about UK urban growth or productivity challenges in the UK. As such, many simple urban economic textbook-type analyses are of limited, little, or no use at all for understanding the UK regional and urban context, as are stylised discussions about so-called MAR-vs-Jacobs externalities, spatial sorting, or ‘people-based versus place-based’ policies.

The UK economy is one of the world’s most interregionally unbalanced industrialised economies (McCann 2016, 2019, 2020; Carrascal-Incera et al. 2020), characterised as it is by an enormous core-periphery structure. UK inequalities between regions are very high by international standards, and inequalities between its cities are also quite high by international standards, but less so than for regions. This is because of the regional spatial clustering, partitioning and segregation of groups of prosperous cities, towns and rural areas into certain regions (broadly the South and Scotland) and the regional spatial clustering, partitioning and segregation of groups of low prosperity cities, towns and rural areas in other regions (Midlands, North, Wales, Norther Ireland).

In particular, the differential long-run performance of UK cities by regional location is very stark. Obviously, there are low prosperity places in the South (Hastings, Clacton, Tilbury, etc.) and prosperous places elsewhere (Ripon, Chester, Warwick, etc.), but what is remarkable is the extent to which these exceptions are almost entirely towns. Indeed, many of the most prosperous places in the Midlands and the North are also towns, while the South also accounts for huge numbers of very prosperous small towns and villages. Unless our policy-narratives closely reflect the realities of the urban and regional challenges facing the UK it is unlikely that policy actions will be effective, and narrative-transfer from the US to the UK is often very unhelpful.

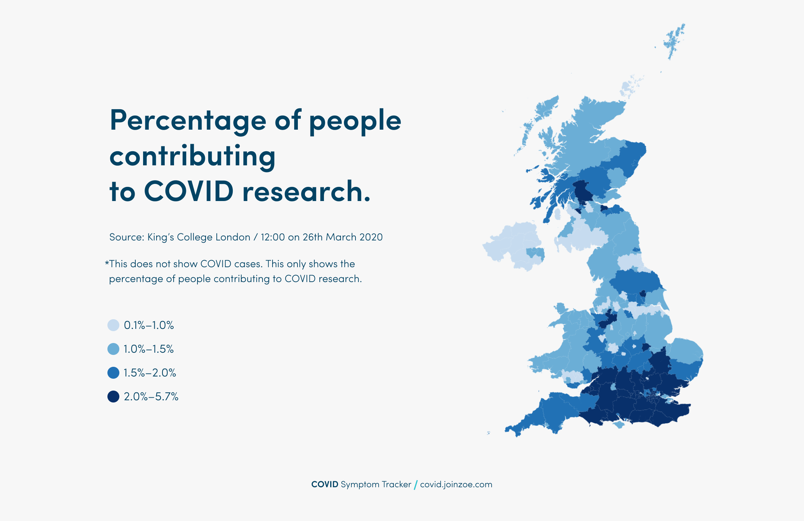

In the case of the current ‘levelling up’ debates these issues are especially important. Given the seriousness and the scale of the situation that we are in, our policy narratives should be led by a careful reading of the literature and a detailed examination of the data on cities (Martin et al. 2018), trade (Chen et al. 2018), connectivity and spatial structures (Arbabi et al. 2019; 2020) in the context of widespread consultation (UK2070 2020) and not on the skills of speechwriters or ideologically-led partisan politics. Brexit, alone, will almost certainly lead to greater long-term interregional inequalities (Billing et al. 2019; McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2020a,b), and Covid-19 is likely to further exacerbate these inequalities.

Our hyper-centralised governance set-up is almost uniquely ill-equipped to address these challenges, and while the setting up of the three Devolved Administrations along with the recent movement towards City-Region Combined Authorities are all steps in the right direction, a much more fundamental reform of our governance systems is required in order to address these challenges. These devolution (not decentralisation!) issues are the difficult institutional challenges that must be focussed on in order to foster the types of agglomeration spillovers and linkages that we would want to see across the country, whereby cities can underpin the economic buoyance of their regional, small-town and rural hinterlands.

A key test of this will be the design of the new ‘Shared Prosperity Fund’, the replacement for EU Cohesion Policy, which for many years had played such an important role in the economic development of the weaker regions of the UK. If the Shared Prosperity Fund programme and processes are devolved, cross-cutting in their focus, allow for specific and significant local tailoring, and are also long-term in nature, then this will be an indication that institutional change is moving in the right direction. But if this Fund is organised in a largely top-down, sectoral, centrally-designed and orchestrated fashion, and is also competitive in nature, then this will clearly indicate otherwise… Let’s see.

References

Ahrend, R., Farchy, E., Kaplanis, I., and Lembcke, A., 2014, “What Makes Cities More Productive? Evidence on the Role of Urban Governance from Five OECD Countries”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2014/05, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

Arbabi, H., Mayfield, M., and McCann, P., 2019, “On the Development Logic of City-Regions: Inter- Versus Intra-City Mobility in England and Wales”, Spatial Economic Analysis, 14.3, 301-320

Arbabi, H., Mayfield, M., and McCann, P., 2020, “Productivity, Infrastructure, and Urban Density: An Allometric Comparison of Three European City-Regions across Scales”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A, 183.1, 211-228

Billing, C., McCann, P., and Ortega-Argilés, R., 2019, “Interregional Inequalities and UK Sub-National Governance Responses to Brexit”, Regional Studies, 53.5, 741-760

Carrascal-Incera, A., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., and Rodríguez-Pose, A., 2020, UK Interregional Inequality in a Historical and International Comparative Context”, National Institute Economic Review, Forthcoming

Chen, W., Los, B., McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R., Thissen, M., van Oort, F., 2018, “The Continental Divide? Economic Exposure to Brexit in Regions and Countries on Both Sides of the Channel”, Papers in Regional Science, 97.1, 25-54

Collier, P., 2018, The Future of Capitalism: Facing the Anxieties, Penguin Books, London

Dijkstra, L., Garcilazo, E., and McCann, P., 2013, “The Economic Performance of European Cities and City-Regions: Myths and Realities”, 2013, European Planning Studies, 21.3, 334-354

Dijkstra, L., Garcilazo, E., and McCann, P., 2015, “The Effects of the Global Financial Crisis on European Regions and Cities”, Journal of Economic Geography, 15.5, 935-949

Glaeser, E.L., 2011, Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, Penguin Press, New York

Martin, R., Sunley, P., Gardiner, B., and Evenhuis, E., and Peter Tyler, 2018, “The City Dimension of the Productivity Problem: The Relative Role of Structural Change and Within-Sector Slowdown”, Journal of Economic Geography, 18.3, 539-570

McCann, P., 2015, The Regional and Urban Policy of the European Union: Cohesion, Results-Orientation and Smart Specialisation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

McCann, P., 2016, The Regional and Urban Policy of the European Union: Cohesion, Results-Orientation and Smart Specialisation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

McCann, P., 2019, “Perceptions of Regional Inequality and the Geography of Discontent: Insights from the UK”, Regional Studies, 53.5, 741–760

McCann, P., 2020, “Productivity Perspectives: Observations from the UK and the International Arena”, in McCann, P., and Vorley, T., (eds.), Productivity Perspectives, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

McCann, P., and Ortega-Argilés, R., 2020a, “Regional Inequality” 2020, in Menon, A., (ed.), Brexit: What Next?, UK in a Changing Europe.

McCann, P., and Ortega-Argilés, R., 2020b, “Levelling Up, Rebalancing and Brexit?”, in McCabe, S., and Neilsen, B., (eds.), English Regions After Brexit, Bitesize Books, London

OECD, 2015, The Metropolitan Century: Understanding Urbanisation and its Consequences, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

OECD, 2019, OECD Making Decentralisation Work 2019, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

ONS, 2017, “Exploring Labour Productivity in Rural and Urban Areas in Great Britain: 2014”, UK Office for National Statistics.

Sandbu, M., 2020, The Economics of Belonging, A Radical Plan to Win Back the Left Behind and Achieve Prosperity for All, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ

UK2070, 2020, Make No Little Plans: Acting At Scale For A Fairer And Stronger Future, UK2070 Commission Final Report, See:

Philipp McCann is Professor of Urban and Regional Economics in the University of Sheffield Management School.

Other posts from the blogged conference:

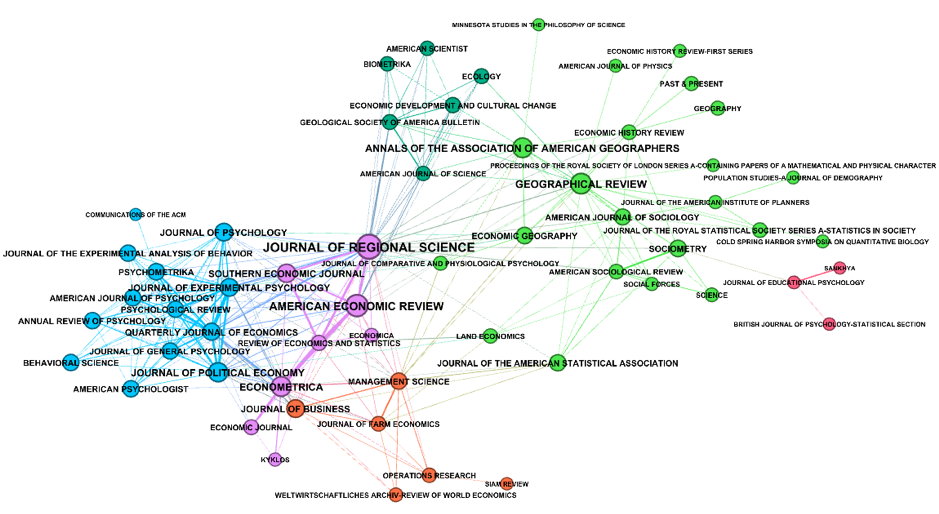

Technology as a Driver of Agglomeration by Diane Coyle

Urban Agglomeration, City Size and Productivity: Are Bigger, More Dense Cities Necessarily More Productive? by Ron Martin

The Institutionalization of Regional Science In the Shadow of Economics by Anthony Rebours

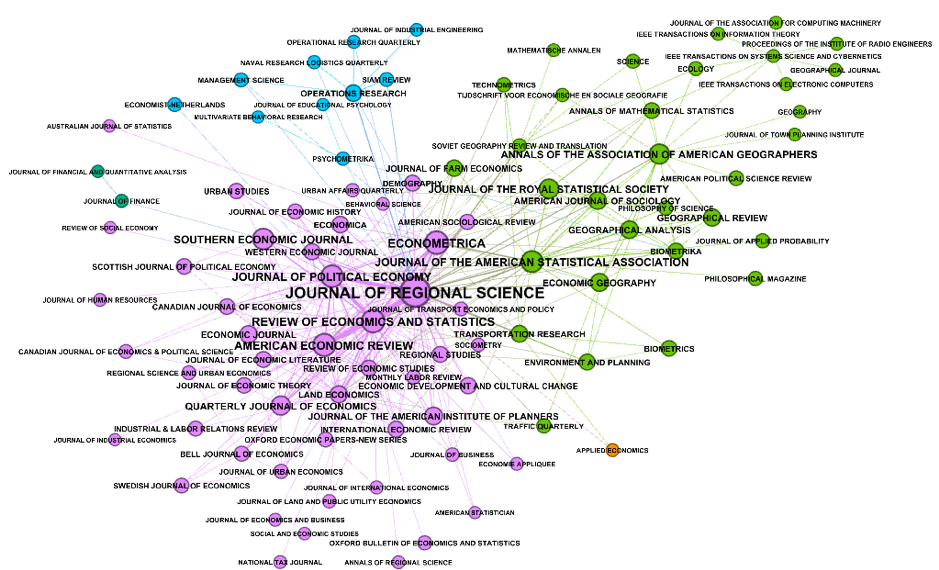

Cities and Space: Towards a History of ‘Urban Economics’, by Beatrice Cherrier & Anthony Rebours

Economists in the City: Reconsidering the History of Urban Policy Expertise: An Introduction, by Mike Kenny & Cléo Chassonnery-Zaïgouche