A documentary by Nakul Singh Sawhney

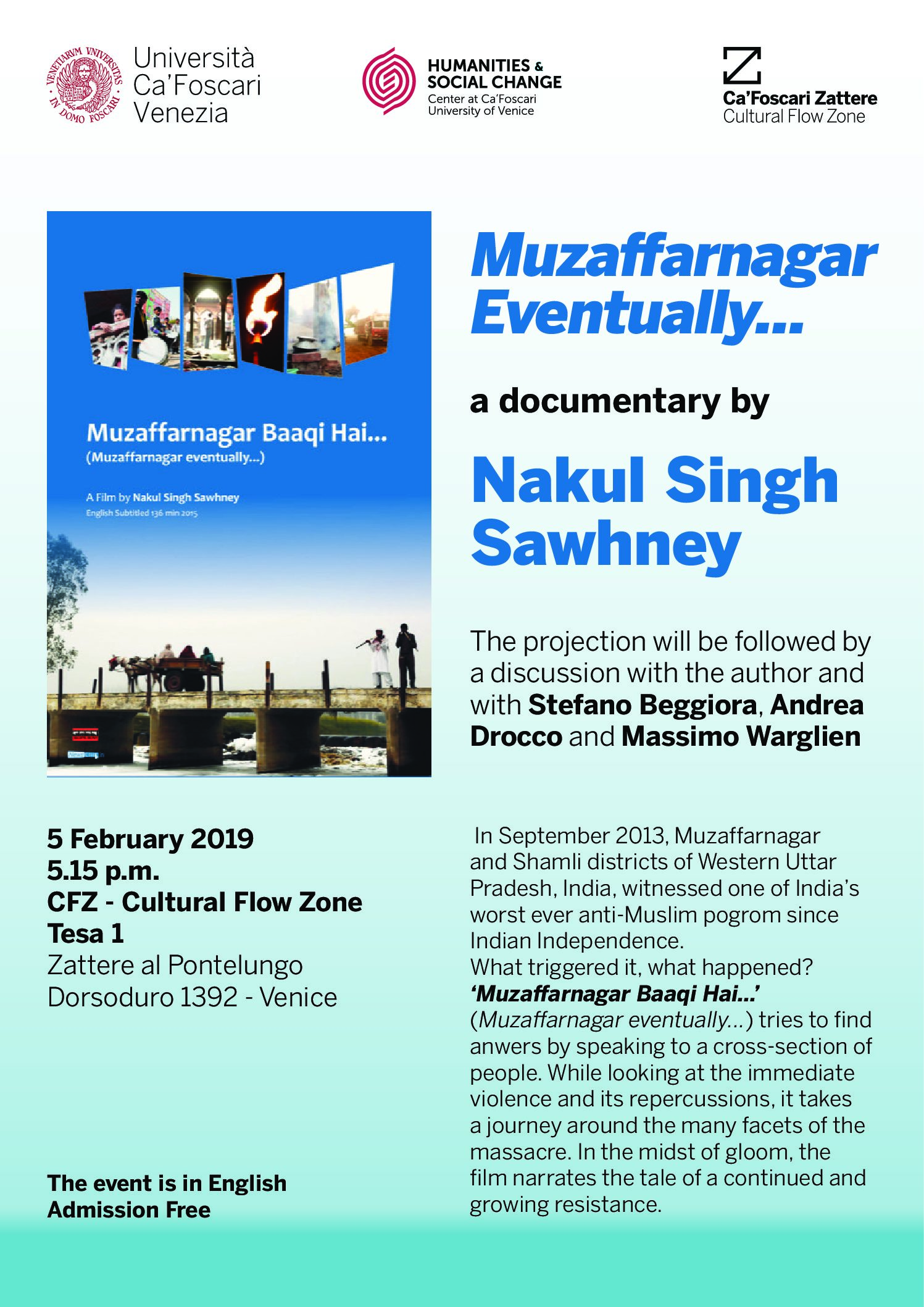

The Venice Center for the Humanities and Social Change presents the screening of the documentary “Muzaffarnagar eventually”, by Nakul Singh Sawhney. Followed by a discussion with the author and with Stefano Beggiora, Massimo Warglien, Andrea Drocco

Venice, 05/02/2019 at 5.15 p.m.

In September 2013, Muzaffarnagar and Shamli districts of Western Uttar Pradesh, India, witnessed one of India’s worst ever anti-Muslim pogrom since Indian Independence. What triggered it, what happened?

‘Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai…’ (Muzaffarnagar eventually…) tries to find anwers by speaking to a cross-section of people. While looking at the immediate violence and its repercussions, it takes a journey around the many facets of the massacre. In the midst of gloom, the film narrates the tale of a continued and growing resistance.

A film by Nakul Singh Sawnhey, English subtitles, 130 mins., India 2015