A few lessons for the coronavirus outbreak from L’Aquila

~ ~ ~

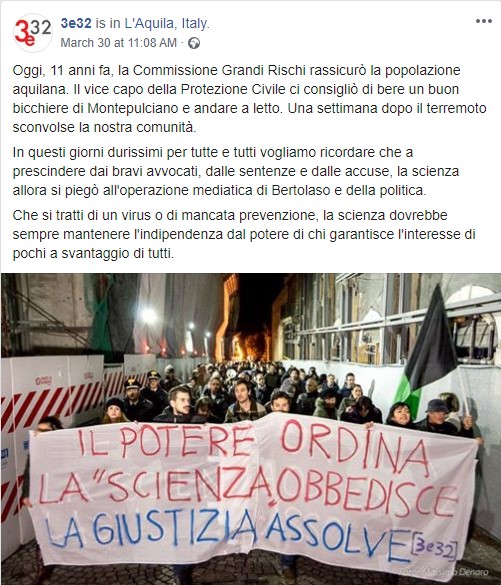

A few weeks ago, a Facebook group called 3e32 and based in the Italian city of L’Aquila posted a message stating: “whether it is a virus or lack of prevention, science should always protect its independence from the power of those who guarantee the interests of the few at the expense of the many”. The statement was followed by a picture of a rally, showing people marching and carrying a banner which read: “POWER DICTATES, ‘SCIENCE’ OBEYS, JUSTICE ABSOLVES”.

What was that all about? “3e32” refers to the moment in which a deadly earthquake struck L’Aquila on April 6th 2009 (at 3:32 in the Morning). It is now the name of a collective founded shortly after the disaster. The picture was taken on November 13th 2014: a few days earlier, a court of appeals had acquitted six earth scientists of charges of negligence and manslaughter, for which they had previously been sentenced to six years in prison.

Even today, many people believe that scientists were prosecuted and convicted in L’Aquila for “for failing to predict an earthquake”, as a commentator put it in 2012. If this were the case, it would be shocking indeed: earthquake prediction is seen by most seismologists as a hopeless endeavour (to the point that there is a stigma associated to it in the community), and the probabilistic concept of forecast is preferred instead. But, in fact, things are more complicated, as I and others have shown. What prosecutors and plaintiffs claimed was that in a city that had been rattled for months by tremors, where cracks had started to appear on many buildings, where people were frightened and some had started to sleep in their cars, a group of scientists had come to L’Aquila to say that there was no danger and that a strong earthquake was highly unlikely. Prosecutors attributed to the group of experts, some of whom were part of an official body called National Commission for the Forecast and Prevention of Major Risks (CMR), a negative prediction, or, in other terms, they claimed that hat they had inferred “evidence of absence” from “absence of evidence”. This gross mistake was considered a result of the experts submitting to the injunctions of the chief of the civil protection service, Guido Bertolaso, who wanted Aquilani to keep calm and carry on, instead of following the best scientific evidence available. Less than a week after the highly publicised expert meeting, a 6.3 magnitude quake struck the city, killing more than 300 people.

The Facebook post, published at the end of March, suggests a link between the management of disaster in L’Aquila and the response to the covid-19 outbreak. The reminiscence was made all the starker by the fact that, just a couple of weeks before the post, Bertolaso had come once again to the forefront of Italian public life, this time not as chief of the civil protection service but as special advisor to the president of the Lombardy region to fight covid-19. But the analogies are deeper than the simple reappearance of the same characters. As during and after all disasters, attributions of blame are today ubiquitous. Scientists and experts are under the spotlight as they were in L’Aquila. Policymakers and the public expect highly accurate predictions and want them quickly. Depending on how a country is doing in containing the virus, experts will be praised or blamed, sometimes as much as elected representatives.

In Italy, for example, many now ask why the province of Bergamo was not declared “red zone”, meaning that unessential companies were not closed down, in late February, despite clear evidence of uncontrolled outbreaks in several towns in the area (various other towns in Italy had been declared “red zones” since February 23rd). Only on March 8th the national government decided to lock down the whole region of Lombardy, and the rest of the country two days later. The UK government has been similarly accused of complacency in delaying school closures and bans on mass gatherings. Public accusations voiced by journalists, researchers, and members of the public provoked blame games between state agencies, levels of governments, elected representatives, and expert advisors. In Italy, following extensive media coverage of public officials’ omissions and commissions in the crucial weeks between February 21st and March 8th, regional authorities and the national government now blame each other for the delay. In a similar way, the UK government and the Mayor of London have pointed fingers at each other after photos taken during the lockdown showed overcrowded Tube trains in London.

It would be easy to argue, with the benefit of hindsight, that more should have been done, and more promptly, to stop the virus, and not only in terms of long-term prevention or preparedness, but also in terms of immediate response. Immediate response to disaster includes such decisions as country-wide lockdowns to block the spread of a virus (like we are witnessing now), the evacuation of populations from unsafe areas (such as the 1976 Guadeloupe evacuation), the stop of the operation of an industrial facility or transport system (such as the airspace closure in Northern Europe after the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2011), or the confinement of hazardous materials (such as the removal of radioactive debris during the Chernobyl disaster). Focusing on this kind of immediate responses, I offer three insights from L’Aquila that seem relevant to understand the pressures expert advisors dealing with the covid-19 are facing today in Britain.

Experts go back to being scientists when things get messy

When decisions informed by scientific experts turn out to be mistaken, experts tend to defend themselves by drawing a thick boundary between science and policy, the same boundary that they eagerly cross in times of plenty to seize the opportunities of being in the situation room. Falling back into the role of scientists, they emphasise the uncertainties and controversies that inevitably affect scientific research.

Although most of the CMR experts in L’Aquila denied that they had made reassuring statements or that they had made a “negative prediction”, after the earthquake, they still had to explain why they were not responsible for what had happened. This was done in several ways. First, the draft minutes of the meeting were revised after the earthquake so as to make the statements less categorical and more probabilistic. Secondly, they emphasised the highly uncertain and tentative nature of seismological knowledge, arguing for example that “at the present stage of our knowledge,” nothing allows us to consider seismic swarms (like the one that was ongoing in L’Aquila before April 6th 2009) as precursors of strong earthquakes, a claim which is disputed within seismology. Finally, the defendants argued that the meeting was not addressed to the population and local authorities of L’Aquila (as several announcements of the civil protection service suggested), but rather to the civil protection service only, who then had to take the opportune measures autonomously. They claimed that scientists only provide advice, and that it is public officials and elected representatives who bear responsibility for any decision taken. This was part of a broader strategy to frame the meeting as a meeting of scientists, while the prosecution tried to frame it as a meeting of civil servants.

In Britain, the main expert body that has provided advice to the government is SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies), formed by various subcommittees, such as NERVTAG (New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group). These groups, along with the chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, have been under intense scrutiny over the past weeks. Questioned by Reuters about why the covid-19 threat level was not increased from “moderate” to “high” at the end of February, when the virus was spreading rapidly and deadly in Italy, a SAGE spokesperson responded that “SAGE and advisers provide advice, while Ministers and the Government make decisions”. When challenged about their advice, British experts also emphasized the uncertainty they faced. They depicted their meetings not as ceremonies in which the scientific solution to the covid-19 problem was revealed to the government, but rather as heated deliberations in which fresh and conflicting information about the virus was constantly being discussed: what Bruno Latour calls “science in the making”, and not what he calls “ready-made science”. For example, on March 17th Vallance stated before the Health and Social Care Select Committee that “If you think SAGE is a cosy consensus of agreeing, you’re very wrong indeed”.

Italian sociologist Luigi Pellizzoni has similarly pointed out an oscillation between the role of the expert demanding full trust from the public and the role of the scientist who, when things go wrong, blames citizens for their pretence of certainty. The result is confusion and suspicion among the public, and a reinforcement of conspiratorial beliefs according to which scientists are hired guns of powerful interests and that science is merely a continuation of politics by other means. In this way, the gulf between those who decry a populist aversion to science, and those who denounce its technocratic perversion cannot but widen, as I suggested in a recent paper.

Epidemiological (like geophysical) expert advice contains sociological and normative assumptions

Expert advice about how to respond to a natural phenomenon, like intense seismic activity or a rapidly spreading virus, will inevitably contain sociological assumptions, i.e. assumptions about how people will behave in relation to the natural phenomenon itself and in relation to what public authorities (and their law enforcers) will do. They also contain normative (or moral) assumptions, about what is the legitimate course of action in response to a disaster. In most cases, these assumptions remain implicit, which can create various problems: certain options that might be valuable are not even considered and the whole process is less transparent, potentially fostering distrust.

In the L’Aquila case, the idea of evacuating the town or of advising the inhabitants to temporarily leave their homes if these had not been retrofitted was simply out of the question. The mayor closed the schools for two days in late March, but most of the experts and decisionmakers involved, especially those who worked at the national level and were not residing in L’Aquila, believed that doing anything more radical would have been utterly excessive at the time. A newspaper condensed the opinion of US seismologist Richard Allen the day after the quake by writing that “it is not possible to evacuate whole cities without precise data” about where and when an earthquake is going to hit. The interview suggested that this impossibility stems from our lack of seismological predictive power, but in fact it is either a normative judgment based on the idea that too much time, money, and wellbeing would be dissipated without clear benefits, or a sociological judgment based on the idea that people would resist evacuation.

The important issue here is not whether a certain form of disaster response is a good or a bad idea, but that judgments of the sort “it is impossible to respond in this way” very often neglect to acknowledge the standards and information on which these are based. And there are good reasons to believe that this rhetorical loop-hole is especially true of judgments that, by decrying certain measures as impossible, simply ratify the status quo and “business as usual”. Our societies rest on a deep grained assumption that “the show must go on”, so that reassuring people is much less problematic than alarming them that something terrible is going to happen. Antonello Ciccozzi, an anthropologist who testified as an expert witness in the L’Aquila trial, expressed this idea by arguing that while the concepts of alarmism and false alarm are well established in ordinary language (and also have a distinctive legal existence, as in the article number 658 of Italian criminal law, which expressly proscribes and punishes false alarm [procurato allarme]), their opposites have no real semantic existence, occupying instead a “symbolic void”. This is why he coined a new term, “reassurism” (rassicurazionismo), to mean a disastrous and negligent reassurance, which he used to interpret the rhetoric of earth scientists and public authorities in 2009 and which he has applied to the current management of the covid-19 crisis.

Pushing the earthquake-virus analogy further, several clues suggest that the scientists that provided advice on covid-19 in Britain limited the range of possible options by a great deal because they were making sociological and normative assumptions. According to Reuters, “the scientific committees that advised Johnson didn’t study, until mid-March, the option of the kind of stringent lockdown adopted early on in China”, on the grounds that Britons would not accept such restrictions. This of course contained all sorts of sociological and moral assumptions about Britain, China, about democracies and autocracies, about political legitimacy and institutional trust. It is hard to establish whether the government explicitly delimited the range of possible policies on which expert advice was required, whether experts shared these assumptions anyway, or whether experts actually influenced the government by excluding certain options from the start. But by and large, these assumptions remained implicit. They were properly questioned only after several European countries started to adopt stringent counter-measures to stop the virus and new studies predicted up to half a million deaths in Britain, forcing the government to reconsider what had previously been deemed a sociological or normative impossibility.

It is true that, in stark contrast to the CMR in L’Aquila, where social science was not represented at all, SAGE has activated its subsection of behavioural science, called SPI-B (Scientific Pandemic Influenza Advisory Committee – Behaviour). Several commentators have argued that this section, by advancing ideas that resonated with broader libertarian paternalistic sensibilities among elite advisors and policymakers, had a significant influence in the early stage of the UK response to covid-19. There is certainly some truth to that, but my bets are that the implicit assumptions of policy-makers and epidemiologists were much more decisive. Briefs of SPI-B meetings in March and February reveal concerns about unintended consequences of and social resistance to measures such as school closures and the isolation of the elderly, but they are far from containing a full-fledged defence of a “laissez faire” approach. The statements reported in the minutes strike for their prudence, emphasising the uncertainties and even disagreements among members of the section. This leads us to consider a third point, i.e. the degree to which experts, along with their implicit or explicit assumptions, managed to exert an influence over policymakers and where able to confront them when they had reasons to do so.

Speaking truth to power or speaking power to truth?

Scientists gain much from being appointed to expert committees: prestige; the prospect of influencing policy; better working conditions; less frequently they might also have financial incentives. Politicians also gain something: better, more rational decisions that boost their legitimacy; the possibility of justifying predetermined policies on a-political, objective grounds; a scapegoat that they can use in case things go wrong; an easy way to make allies and expand one’s network by distributing benefits. But although both sides gain, they are far from being on an equal footing: expert commissions and groups are established by ministers, not the other way around. This platitude testifies to the deep asymmetry between experts and policymakers. We have good reasons to think that, under certain circumstances, such an asymmetric relation prevents scientific experts to fully voice their opinions on the one hand, and emboldens policymakers into thinking that they should not be given lessons by their subordinates on the other. Thanks to the high popularity of the 2019 television series Chernobyl, many now find the best exemplification of such arrogance and lack of criticism in how the Ukrainian nuclear disaster was managed by both engineers and public officials.

There is little doubt that something of the sort occurred in L’Aquila. Several pieces of evidence show that Bertolaso did not summon the CMR meeting to get a better picture of the earthquake swarm that was occurring in the region. In his own words, the meeting was meant as a “media ploy” to reassure the Aquilani. But how could he be so sure that the situation in L’Aquila did not require his attention? It seems that one of the main reasons is that he had his own seismological theory to make sense of what was going on. Bertolaso believed that seismic swarms do not increase the odds of a strong earthquake, but on the contrary that they decrease such odds because small shocks discharge the total amount of energy contained in the earth. Most seismologists would disagree with this claim: low-intensity tremors technically release energy, but this does not amount to a favourable discharge of energy that decreases the odds of a big quake because magnitudes are based on a logarithmic scale, and a magnitude 4 earthquake releases a negligible quantity of energy compared to that released by a magnitude 6 earthquake (and, more generally, to the energy stored in an active fault zone). But scientists appear to have been much too cautious in confronting him and criticising his flawed theory. Bertolaso testified in court that in the course of a decade he had mentioned the theory of the favourable discharge of energy “dozens of times” to various earth scientists (including some of the defendants) and that “nobody ever raised any objection about that”. Moreover, both Bertolaso’s deputy and a volcanologist who was the most senior member of the CMR alluded to the theory during the meeting and in interviews given to local media in L’Aquila. A seismologist testified that he did not feel like contradicting another member of the commission (and a more senior one at that) in front of an unqualified public and so decided to change the topic instead. Such missed objections created the conditions under which the “discharge of energy” as a “positive phenomenon” became a comforting refrain that circulated first among civil protection officials and policymakers, and then among the Aquilani as well.

Has something similar occurred in the management of the covid-19 crisis in Britain? As no judicial inquiry has taken place there, there is only limited evidence that does not authorize anything other than speculative conjectures. However, there are two main candidate theories that, although lacking proper scientific support, might have guided the actions of the government thanks to their allure of scientificity: “behavioural fatigue” and “herd immunity”. As mentioned above, many think that behavioural fatigue, according to which people would not comply with lockdown restrictions after a certain period of time so that strict measures could be useless or even detrimental, has been the sociological justification of a laissez faire (if not social Darwinist) attitude to the virus. But this account seems to give too much leverage to behavioural scientists who, for the most part, were cautious and divided on the social consequences of a lockdown. This also finds support in the fact that no public official to my knowledge referred to “behavioural fatigue” but rather simply to “fatigue”, without explicit reference to an expert report or an authoritative study (as a matter of fact, none of the SPI-B documents ever mentions “fatigue”). I’d like to propose a different interpretation: instead of being a scientific theory approved by behavioural experts, it was rather a storytelling device with a common-sense allure that allowed it to get a life of its own among policy circles, ending up in official speeches and interviews. The vague notion of “fatigue”, which reassuringly suggested that the country and the economy could go on as usual, might have ended up being accepted with little suspicion by many experts as well, especially those of the non-behavioural kind. The concept could have served both as a reassuring belief for public officials and as an argument that could be used to justify delaying (or avoiding) a lockdown. The circulation of “herd immunity” might have followed a similar pattern. Although a scientifically legitimate concept, there is evidence that, along with similar formulations such as “building some immunity”, it was never a core strategy of the government, but rather part of a communicative repertoire that could be invoked to justify a delay of the lockdown as well as measures directed only at certain sections of the population, such as the elderly. Only on 23 March the government changed track and abandoned these concepts altogether, taking measures similar to other European countries.

~ ~ ~

The analogy between how Italian civil protection authorities managed an earthquake swarm in L’Aquila and how the British government responded to covid-19 cannot be pushed too far. Earthquakes and epidemics have different temporalities (a disruptive event limited in space and time on the one hand, a long-lasting process with no strict geographical limits on the other), are subject to different predictive techniques, and demand highly different responses. While a large proportion of Aquilani blamed civil protection authorities immediately after the earthquake, Boris Johnson’s approval rating has improved from March to April 2020. However, what happened in L’Aquila remains, to paraphrase Charles Perrow, a textbook case of a “normal accident” of expertise, i.e. a situation in which expert advice ended up being catastrophically bad for systemic reasons, and notably for how the science-policy interface had developed in the Italian civil protection service. As such, there is much that expert advisors and policymakers can learn from it, whether they are giving advice and responding to earthquakes, nuclear accidents, terrorism, or a global pandemic.