In November 2019, Fodé Beaudet from the Canadian Foreign Service Institute from Global Affairs Canada visited the UK as part of a project to better understand how we can design, facilitate and evaluate our work to support behavioural change at the individual, group or system level. He met with Anna Alexandrova and Hannah Baker at the University of Cambridge to discuss overlaps between his own work and the Expertise Under Pressure project. Consequently, he kindly agreed to answer the questions that we put forward during our ‘Expert Bite’ discussions as a blog post, and we hope that there will be further collaboration in the future.

Fodé Beaudet

Senior Learning Advisor, Centre for Intercultural Learning, Canadian Foreign Service Institute (CFSI) at Global Affairs Canada

Biography

Fodé Beaudet is a Senior Learning Advisor at the Centre for Intercultural Learning with Global Affairs Canada (GAC). He has extensive experience in designing and facilitating multi-stakeholder initiatives around the world – themes include train-the-trainer platforms to facilitate change, Whole of Government Approaches to strategic collaboration, navigating through Complex Adaptive Systems and strengthening the intercultural effectiveness of professionals working overseas. Clients include international NGOs, global networks and institutions, foreign governments, the defence sector, research institutions and partner agencies affiliated with GAC. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of the Institute for Performance and Learning (I4PL).

Adult learning approaches and intercultural effectiveness

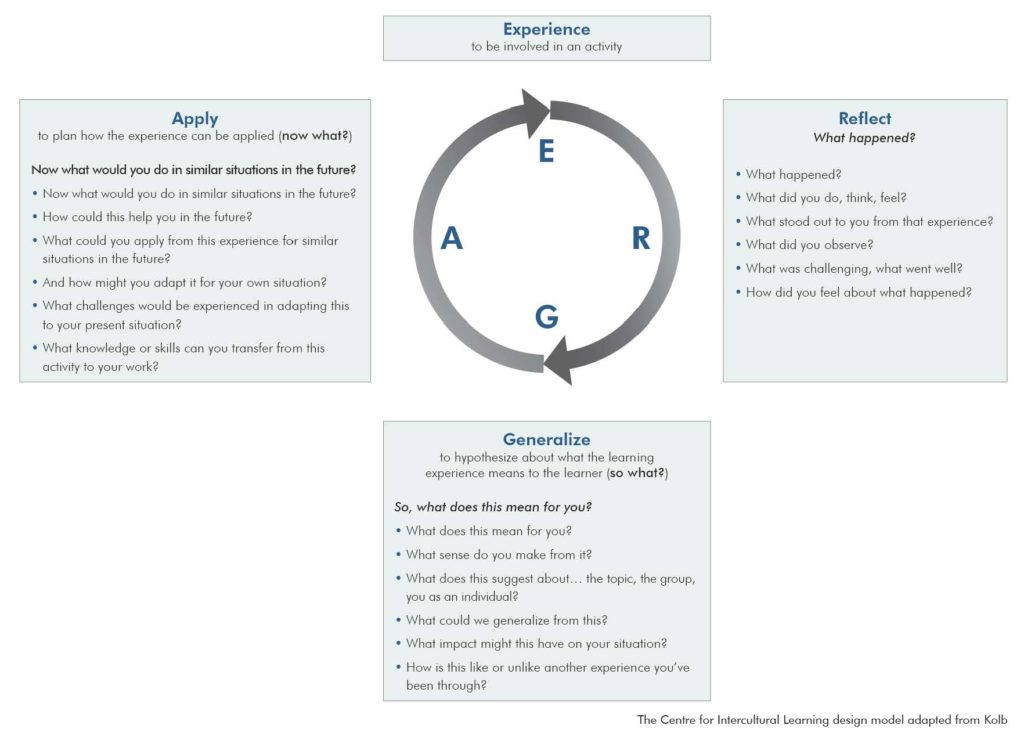

For the purpose of this blog, I will focus mostly on our adult learning approach to strengthening intercultural effectiveness competencies. Established in 1969, the Centre for Intercultural Learning (CIL) is Canada’s largest provider of intercultural and international training services for internationally-assigned government and private-sector personnel. One of the CIL significant research products was the development of a competency-based model for intercultural effectiveness, the profile of the intercultural effective person (Vulpe, T., Kealey, D., Protheroe, D., & Macdonald, D. (2001). This model, delivered with an experiential learning approach (Kolb, 1984), has proven successful to help prepare individuals for short- or long-term missions. According to Kolb, “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (1984, p. 38). The experiential learning model, adapted from Kolb, invites learners in a series of cycles, as indicated below.

The expert-knowledge content is often integrated at the ‘Generalize’ stage of the ERGA learning cycle. At this point, the expert has a good overview of the knowledge in the room, and she or he can best distill valuable insights to complement what is already known. This may involve validating current knowledge, nuancing some points of views, or challenging what was said. The ‘application’ step invites learners to discuss in groups or in solo how to apply what they have learned and integrates their peers’ knowledge as well as the expert’s contribution. Thus, the cycles of learning loops look more like a spiral than a circle.

1. Considering your research and/or work in practice, what makes a good expert?

Understanding the andragogic approach to learning: comfort with emergence. We distinguish good intercultural experts by their ability to acknowledge and recognize how the content of their contribution can reinforce the knowledge and experience in the room. An expert content does not always have to be elaborated at length, because learners may have reached similar insights. A good expert will challenge, validate, nuance or enrich content. As such, comfort with emergence means a predisposition for active listening and demonstrate agility based on what is said in the moment. As for an expert facilitator, comfort with emergence and understanding andragogic approach to learning also applies. For instance, our train-the-trainer approach involves very little content from the facilitator. A facilitator will rarely speak for more than 5 minutes. In a train-the-trainer format, learners assess, design, facilitate and evaluate their work collaboratively, in real-time. Reflective practice encourages learners to deepen their self-awareness about the experience. I recall when I was first introduced to this work, co-facilitating a train-the-trainer: my first reaction, when learners were struggling with a task, requesting an example, was to provide one. And then, I got into a murky water: how would you proceed next? My gifted co-facilitator at the time took me to the side and reminded me: let them struggle. Let them figure it out. This is important. In this particular format and context, an expert facilitator has to hold and suspend their ideas or creativity. It’s about setting the container for learners to shine. The less an expert facilitator says, is seen, the better. Then, learners become the experts, taking ownership and responsibility to finding solutions instead of asking for them.

I also recall a learner asking at the start of a train-the-trainer workshop regarding expectations: “How can I deal with difficult people?” At the end of the workshop, the learner shared this, which I paraphrase “I think it is me, who can be difficult sometimes”. In other words, we are not isolated from the system we wish to intervene. We are part of any system. And as long as we project “fixing” to be solely about others, we may miss an important blind spot. Which means making discomfort and silence your friend. During another train-the-trainer in the Middle East, a man shared a powerful testimony. He pointed to a woman in the group, and said for all to hear:

“Before coming here, I didn’t think women could lead. Not only were you a leader, working with two men, but I have two daughters and I hope someday they will be like you.”

This is the potential transformative of participatory processes when learners are taking an active part in co-creating with others. Hierarchy breaks down. Self-organization is encouraged. And mental models are challenged. Because the expertise is across the room.

Inquisitive mind. The value of an expert’s skilled questions to better understand the learner profile. In contrast, an expert with a set presentation seeking to repurpose what she or he has already repeated may not be a good fit.

Humility. Here is an anecdote to make the point. At the beginning of an intercultural course about an Asian country, the intercultural expert said: “If someone tells you they know the country, they don’t know the country.” He described at length his experience, but only to convey how he felt short of truly understanding the culture and that he had a lot to learn. A learner, who was born and raised in that particular country, said to the expert for everyone to hear: “You understand the country very well.” This humility, in some circles, may be counter-intuitive. However, when engaging with understanding what it means to be effective across cultures, humility promotes curiosity and deepens one’s inquiry to what are complex webs and layers that evolve and transform over time. In contrast, an assertiveness and certainty about culture in general terms can do a disservice to learners, reinforcing assumptions and inadvertently promoting ill-conceived predictive behaviours. Here is one example about how the model can be adapted. Years ago, I was collaborating with a client hosting a Japanese delegation. One of their goals was to come up with a partnership agreement. They sought our services to learn about Japanese culture. We had less than a day. I worked with an expert facilitator and an intercultural expert with knowledge about Japanese culture to design an approach. Given the client’s end goal, we devised a plan where the client was given an opportunity to reflect on how their current approach relates to Japanese culture. In the morning, they learned key features about the culture. And then, in the afternoon, we asked the client to describe how they intended to host their counterparts, dividing the task into three categories: activities before the delegation arrives, during, and after. And they presented back their findings, strategies and questions to the intercultural expert. Details, like the value of greeting the delegation at the airport surfaced. Reviewing lunch time allocation, setting up social activities, and not just work-related activities. But the most insightful learning from the client was the need to reframe their goal: given the decision-making process they had learned about, it was unrealistic to expect a partnership agreement so soon. Therefore, emphasis on hosting was about nurturing and building relationships. I give a lot of credit to the client, who, instead of forcing their approach, reframed the goal itself. And the intercultural expert had the wisdom to let learners surface their assumptions, complementing their strategies with her own insight.

2. What are the pressures experts face in your field?

No one organization nor individual can understand nor convey the full extent of what needs to be learned. Hence the importance to acknowledge the boundaries of expert knowledge while being confident in what they can contribute. Problems are not solved with the help of one expert, but through the collaboration among diverse expertise. I’ll weave some examples of our work and research in addressing complex problems in a multi-stakeholder context. Here are a few pressures experts face:

Attribution:how do you communicate the value of your expertise, when the result is part of a larger ecosystem? How important is it for the expert to be visible, vs promoting the visibility of others?

Tensions between asking good questions vs offering answers.Inevitably, someone will want to know: can you tell me exactly what I need to say? What I need to do? How will someone respond if I do X? What if I do Y? It dependsdoesn’t answer the question and can be frustrating. And yet, it dependscan also be closer to the truth than coming up with a reassurance in the moment that can be deceptive later. Probing further questions about what is being asked may lead to better answers. It’s also tricky: aren’t you supposed to be an expert? Aren’t you supposed to know?

This is where experts and clients may collude: in the search of an easy solution, in the effort to prove that something is done, the lure of pursuing the wrong problem can provide an illusory solace, and therefore lead both experts and clients to ‘tick the box’, indicating that ‘actions’ were made.

Contractual agreement. Building on the previous points, experts feel pressure to operate within the contractual agreement they are accountable to. Yet, when facing complex problems, the emergence of unexpected scenarios may require reframing what was understood to be the problem. So if the contract has little flexibility, a new understanding about a problem cannot be accounted for. So experts are torn between the reality of what they see, and the murkier expectations of what they should deliver.

Hence, to make the most of a good expert, there is also a need for a good procurement process. Faulty procurement, with little flexibility, can turn the best experts into the worst. All with good intentions. For example, a common reflex for easy solution is training. Yet, in many instances, training is not the answer. Here’s an example about how a mental model shifted as a result of incorporating generative dialogues in our train-the-trainer workshops. Generative dialogues put emphasis on a shared understanding about a problem or an inquiry, to reflect on the collective wisdom, and propose actions to move forward. David Bohm (2013), among others, have written extensively about the value of dialogue. A key feature of generative dialogue is that neither the problem/inquiry nor the solutions are predetermined. Everyone’s voice is valued. The physical environment is key: conversations in small groups or in a large circle, as oppose to lecture-style format. During one of the train-the-trainer in the Horn of Africa, a learner approached me, after experimenting with such approach, saying; “You mean, we don’t need training? We can have dialogue?” In some instances, yes. Training has its place too. Lecture-style have their place too. It’s a matter of finding the appropriate response to the problem at hand. Generative dialogue requires dealing with discomfort, with not knowing what the answer will be. In other words, generative dialogue is useful when dealing with complex problems. And perhaps paradoxically, while it’s an ancient practice well known among First Nations communities, it may also be part of a practice for approaching the future.

3. Have you observed any significant changes occurring in recent times in the way experts operate?

The concept of the wisdom of the crowd has certainly grown. In the context of how experts operate, I will say that there is a greater openness and inquisitiveness about how their part fit into a broader picture. I noticed several experts exemplified in Ed Schein’s (1999) stance of the process consultant, whereby an expert will help clients identify the problem properly. I also noticed this stance when experts work in the field of systems thinking. This may also reflect experts gaining knowledge not only about the content they can provide, but the process they can support.

The rise of social labs is perhaps an indication of an emerging ‘expertise’; the art convening space for experts to co-create. One of many examples would be the Art of Hosting. A change I see is the blend of expert content and the expert skilled to hold the container. I remember working with a client system that insisted to push the boundaries of what is possible. They were seeking to create new theories of change for education in Africa. In this context, all participants had a voice, whether former ministers of education, deans, vice-deans, farmers, CEOs or students. In hindsight, this reflected the complementary role of expertise. It’s alluring for an expert to define what should be done. But in some instances, a community, a collective, or a multi-stakeholder representation is needed to name, envision and frame a compelling and shared understanding towards a future horizon. Building from a shared vision and understanding, the role of experts is clearer. But if we name or assume a particular expert model too soon and especially prior to a shared understanding, then the risk is to fall into the trap of using a fashionable trend that serves a model rather than the actual problem or appreciative inquiry.

Finally, I also think that Donald Schön, in his thought-provoking book in 1987, the Reflective Practitioner, offered insights still relevant today: the growing shift of technical knowledge to address complex problems. And as a result, a more reflective professional stance, whereby framing the problem is of the upmost importance.

4. Do you envision any changes in the role of experts in the future?

It’s unclear for me if the future will look like the continuation of a trend, a pattern, or if there will be significant upheaval or sudden bifurcation. One factor that may influence the role of experts is our relationships with evidence and facts. The other is the independence in which experts operate: to what extent is the ecosystem in which experts will evolve is vulnerable to collusion, unconsciously, or implicitly? In the latter case, experts may serve to prove a point of view, rather than enrich point of views.

In the context of intercultural effectiveness, I foresee the continuation of expanding beyond the classroom and the virtual environment to include learning journeys and more action learning oriented approaches. I could see strengthening the model of experiential learning to include mindfulness, where sensemaking is not limited to what one thinks or feels, but also inquisitiveness about the body’s way of learning. This would call for more immediate attention to presence, in order to witness and discern how we are influenced by past experience, which affects how we project into the future. However, to embrace a more direct perception with less filter is an uncomfortable place to be, to hold, but one rich with clarity.

Overall, I see a growing emphasis on two streams that have been more or less separated: technical and process-oriented expertise. The latter is about holding the container, sensemaking, facilitation, convening and hosting skills. The former, is delving deeper into system dynamics and social network analysis, where culture is understood as systems, transcending borders. Here’s an example of what I’ve learned from experts in these fields through work projects; when we integrate the lens of systems and how nodes interact with each other, we see common features among patterns: systems are self-reinforcing. Systems have a purpose, which is to survive. The purpose of a system is what it does, once said the cyberneticist Stafford Beer. This has implications for living in a turbulent environment where survival instincts are heightened: if the purpose of a system is a system, then perhaps change happens by understanding patterns and purpose beyond their perceived shared values. I found the experience of collaborating with experts in social network analysis while inviting stakeholders into a sensemaking analysis revealing.

I wouldn’t be surprised, in the future, to witness more and more of these conversations among technical expertise and process-oriented approaches. Perhaps a process without good content is as useless as good content without a proper process to make sense of it.

References

Bohm, David. (2013). On Dialogue.Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning experience as a source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Schein, E. H. (1999). Process consultation revisited: Building the helping relationship. New York: Addison- Wesley.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action.United States of America: Basic Books.

Vulpe, T., Kealey, D., Protheroe, D., & Macdonald, D. (2001). A Profile of the Interculturally Effective Person. Centre for Intercultural Learning. Canadian Foreign Service Institute.