An Expertise Under Pressure Workshop

11 February 2020

Cripps Court, Magdalene College, Cambridge

Organised by Hannah Baker, Rob Doubleday and Emily So

The ‘Disaster Response | Knowledge Domains and Information Flows’ workshop on the 11 February 2020 formed part of the Expertise Under Pressure Project (EuP), specifically the Rapid Decisions Under Risk case study.

The aim of this event was to explore the different knowledge domains and information flows in the context of disaster response situations, such as the immediate aftermath of an earthquake or volcano, or the ongoing response to the coronavirus, which has since become the global pandemic known as COVID-19. A reflection in light of this is provided at the end of this blog following a description of the workshop’s proceedings. Attendees were from a range of disciplines, including representatives from the Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP) who have written their own summary of the day.

Workshop questions:

In the context of disaster response:

- What type of knowledge is and should be used?

- What constitutes as an expert?

- How is and should uncertainty be factored into decisions and communicated?

- What happens to, and should happen to, knowledge after it is produced and the event has taken place?

Speaker Session 1

Hannah Baker

Emily So

Amy Donovan

Introduction

Hannah Baker is a Research Associate at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities (CRASSH) at the University of Cambridge. She opened the day by providing an overview of the EuP project. The relevance of the topic was conveyed through a display of screenshots comprising multiple newspaper headlines referring to the use of experts in dealing with the coronavirus outbreak in, at the time (February 2020), Wuhan China. The headlines were also used to highlight that these experts are not always in agreement with one another, with an example being predictions of when the peak of the infection would be.

A theoretical context for disaster management arguing that there are no ‘natural disasters’ was then provided. There are natural events, such as a volcanic eruption, but these turn into disasters due to social factors that increase the vulnerability of a population. Within the disaster management cycle there are four stages: prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response, and rehabilitation and recovery. Although this workshop focused on the response, the other stages are not mutually exclusive. In the response stage, the decision-making environment is uncertain, under time-pressure and can result in high impacts (Doyle, 2012).

The reasons for referring to 1) ‘Knowledge Domains’ and 2) ‘Information Flows’ in the workshop’s title were then outlined. To address the first part, disaster research regularly discusses the use of scientific expertise in decisions-making, however it is also recognised that information can come from elsewhere. For example, Hannah displayed a newspaper headline referring to the use of ‘indigenous expertise’ in combating the recent Australian Bushfires.

In disaster management literature there is also an emphasis on the need to create networks before an event takes place to establish trust and facilitate the flow of information when that event happens. The concept of information flows can be extended further as the communication of knowledge is not only communicated to and between decision-makers but also the wider public. An issue here being ‘fake news’ and as put by the Director General of the World Health Organisation in response to misinformation about the coronavirus, now is the time for “facts, not rumours”.

Is knowledge driving advice or vice versa in the field of natural disaster management?

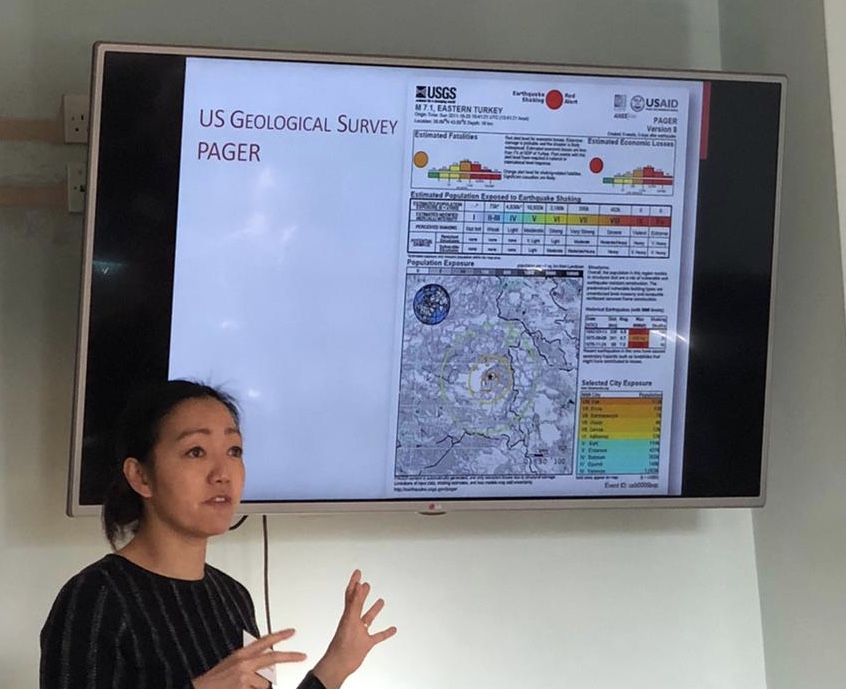

Emily So is the project lead for the ‘Rapid Decisions Under Risk’ case study, a Reader in the Department of Architecture at the University of Cambridge and a chartered civil engineer. Following the 2015 Nepal Earthquake, Emily was invited by the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) to contribute her expertise on earthquake casualty modelling and loss estimations. SAGE provides scientific and technical advice to decision-makers during emergencies in the Cabinet Office Briefing Room (COBR). ,

Although casualty models take into account structural vulnerability, seismic hazards and the social resilience, Emily highlighted that the interpretation of these and use for loss estimations is often based on knowledge and experience. She emphasised that those making these interpretations are unlikely to always have experience in the country in which the earthquake has occurred.

Emily’s participation in SAGE led her to question 1) What happens to the gathered advice? 2) What is the process of turning this information into decisions and actions? 3) What if we are wrong? These questions formed the origins of the EuP case study and use of experts in disaster response situations.

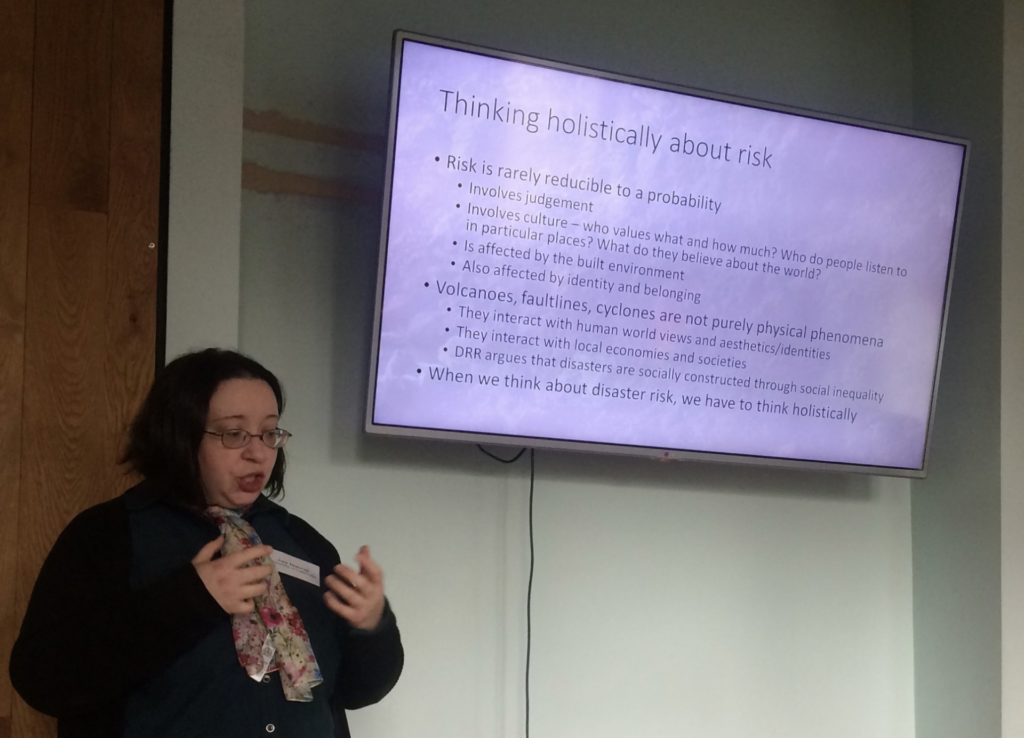

Thinking holistically about risk and uncertainty

Amy Donovan is a multi-disciplinary geographer, volcanologist and lecturer at the University of Cambridge. During the workshop she presented arguments from her recent paper: ‘Critical Volcanology? Thinking holistically about risk and uncertainty’. She reiterated that there are no natural disasters and then moved on to question what creates good knowledge, emphasising that risk in itself is incomplete. For instance, in her paper she states:

‘the challenge of volcanic crises increasingly tends to drag scientists beyond Popperian science into subjective probability‘ Donovan (2019, p.20)

Historically, the physical sciences have been better accepted as they can be modelled, whilst the social sciences are difficult to measure as they are people studying people and therefore subjective. However, Amy argued that risk is a social construction in itself and that datasets can be interpreted in different ways due to people’s experiences working in different locations around the world. She also affirmed that the social sciences need to be brought in at the start of the decision-making process, rather than at the end (which is commonly the case now and often only for communication purposes). A dialogue needs to be happening before a disaster even happens.

Amy also discussed the impact on the people being consulted as experts in disaster response situations as they can be affected by this as the advice that they give can affect other’s lives. This is why the transfer of knowledge is important as its often difficult for scientists to control which parts of knowledge are taken forward and how that is communicated.

Speaker Session 2

Robert Evans

Dorothea Hilhorst

Nature and use of scientific expertise

Robert Evans is a Professor in Sociology at the Cardiff University School of Social Sciences, specialising in Science and Technology studies. The focus of his presentation built upon previous work on the ‘Third wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience’. Two key concepts within this paper are the notions of contributory and interactional expertise. The former is often the accomplished practitioner who can perform practical tasks and the latter was a new idea based on linguistic socialisation as the expert is able to communicate and speak fluently about practical tasks.

As no one can be an expert in everything, in their paper Collins and Evans state:

‘The job, as we have indicated, is to start to think about how different kinds of expertise should be combined to make decisions in different kinds of science and in different kinds of cultural enterprise‘ Collins & Evans (2002, p.271)

Robert also spoke about legitimacy and extension, and how legitimacy can increase as more voices are included, yet, poses the question whether the quality of technical advice decreases if ‘non-expert’ inputs are given too much weight. This ties in with the concept of robust evidence. Although Robert spoke before COVID-19 became a global pandemic, this is now as relevant as ever as he put forward questions about how we handle controversial advice and that scientific experts will not always reach a consensus.

Social Domains of disaster knowledge and action

Dorothea Hilhorst is a Professor of Humanitarian Aid & Reconstruction at the International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) of Erasmus University Rotterdam. Dorothea’s paper, published in 2003, ‘Responding to Disasters: Diversity of Bureaucrats, Technocrats and Local People’ led to us thinking about the use of different knowledge domains in disaster response situations. Dorothea reflected upon this by linking the domains of knowledge to power, and also on how we see a disaster as alliances between the domains, such as science, political authorities, civil society and community groups. Within her paper, she states:

‘Instead of assuming that scientific knowledge is superior to local knowledge, or the other way around, a more open and critical eye needs to be cast on each approach…disaster responses come about through the interaction of science, governance and local practices and they are defined and defended in relation to one another‘ Hilhorst (2003, p.51)

Like Amy Donovan, Dorothea emphasised that there are ‘no natural disasters’ by referring to the change in disaster paradigms through time and also speaking about the concept of Disaster Risk Creation (DRC). This shift went from an attention to behavioural studies in the 1950s, the entry of vulnerability followed by community to the paradigm in the 1980s, a focus on climate change in the 1990s and then a turn to the concept of resilience in the 2000s. Thea noted that in her own work she focuses on when disasters and conflict happen at the same time whereby the governance is even more complex in these situations.

Speaker Session 3

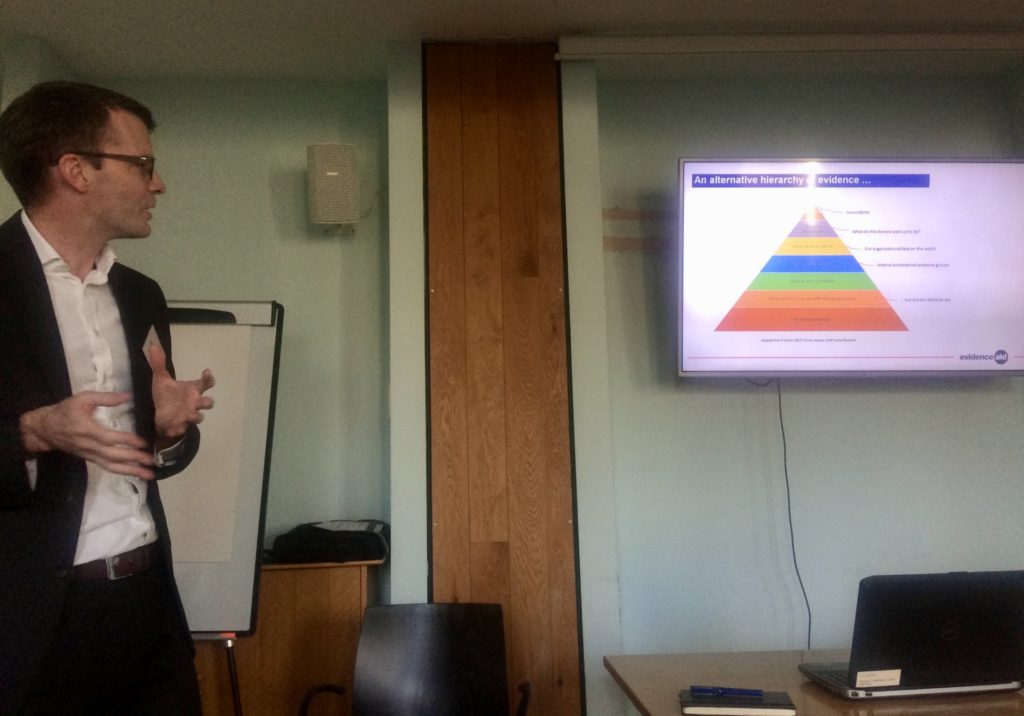

Disasters, Evidence and experts: A case Study from Evidence Aid

Benjamin Heaven Taylor is the Chief Executive Officer of Evidence Aid, an international NGO that works to enable evidence-based decision-making in humanitarian settings. Ben opened the discussion by describing the humanitarian ecosystem which includes (but is not limited to) the UN, International NGOs, research bodies, as well as local civil society, private sectors and individuals. He showed a pyramid reflecting the hierarchy of evidence. Due to the time constraints of a disaster response situation, expert evidence is frequently used but there is often a weak research-evidence base, meaning that there is little basis for challenging experts’ views. The research-evidence base is often weak due to it being inaccessible, ‘patchy’ and there being political barriers. However, Ben emphasised that the use of experts isn’t necessarily a bad thing and that…

‘When used properly experts can be a vital mediator between evidence (which can be a blunt instrument) and practice. But experts (including scientists) can be influenced by bias, just like anyone‘ Taylor (2020) – Workshop presentation

The presentation concluded by referring to Evidence Aid’s theory of change with the overarching idea being that before, during and after disasters, the best available evidence is used to design interventions, strategies and policies to assist those affected or at risk.

Focus Group Discussions

As part of the day, we had three separate focus group discussions. The facilitator for each group opened with some thoughts provided by Emma Doyle, a Senior Lecturer at the Joint Centre for Disaster Research at Massey University, New Zealand (Emma’s answers are provided in a separate blog post). Each group then built upon these initial thoughts and discussed the question. Summaries of discussion topics are provided below.

In the context of disaster response…

What type of knowledge is and should be used?

Initially the conversation separated knowledge domains into two streams – science and indigenous knowledge. However, this separation was critiqued and considered to be a reductionist way of thinking. Although it was acknowledged it is important to be clear where knowledge has come from and the conditions in which it was created, it was suggested that perhaps it is more useful to think about knowledge as a network of clusters that may or may not be talking to one another.

Disaster response is an integrated problem and in a time constrained environment, it’s someone’s job to bring this separate and sometimes conflicting information together. As part of this role, the framing of the initial questions is vital in determining what knowledge is collected. A key issue with the collection of knowledge is credibility and the need to demonstrate trustworthiness. For one engineer in the group, model makers often do not have the ‘luxury’ of choosing data, and if they do, the determination of reliability is often subjective and determined by expert judgment.

How is and should uncertainty be factored into decisions and communicated?

The level of communication for uncertainty impacts the confidence that the public have in decision-makers and consequently the level of trust. The question of how much and how uncertainty is communicated was raised. For example, whether the uncertainty is presented as a number or through graphics is dependent on the type of event and the cultural context. Perhaps there is also a balance to be struck between communicating the full range of possibilities for transparency and not supplying too much information, which can cause cognitive overload.

Examples were given of model makers who are keen to communicate all uncertainties rather than make the decision themselves. Another example is that once a decision is made, if an immediate response is required, people ‘on the ground’ may just prefer to be told what to do and given instructions. A potential way in which the communication of uncertainty can be balanced is a layered approach, which is sometimes used in healthcare. Highlighting the information that needs to be known but then allowing access to more detailed information if a patient wants to see the same level of detail as their clinician. However, it was recognised that in a time pressured situation such as disaster response, this will be more difficult to formulate. Fundamentally, the question of communicating uncertainty was described as a moral and ethical judgment.

What happens to, and should happen to, knowledge after it is produced and the event has taken place?

This focus group began by discussing the initial collection of knowledge and how this is often based on visibility or access to data or individuals. In some cases, ‘experts’ might be selected because of the institution they are from or willingness to interact with the media but this may not make them the most appropriate person to answer the questions at hand. In any case, wherever the knowledge has come from, transparency is key and the group felt that the general public can act out of panic if they do not feel informed. If the release of information to the public is staggered, this can lead to a loss of empowerment. However, this is then balanced against communicating what is necessary. In many cases, the scientific experts should not be expected to communicate directly with the public, often this requires a mediator. If there is not a clear and hard line from the government, fake news and rumours are likely to be a major issue.

Reflections in light of COVID-19 being declared a global Pandemic

Clearly the topics discussed in the workshop are highly relevant to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In the UK, COVID-19 has been declared as a national emergency and at the time of writing I am socially distancing myself under the new strict governmental measures and working from home. COVID-19 is relevant to all the questions posed in our workshop, and to the content of the presentations and focus groups. I will now draw some links with the talks given by each guest speaker, but recognise that there are many more!

Amy talked about the transfer of knowledge and how that can then be out of the expert’s control once imparted. Due to the popularity of social media, there have been widespread issues of miscommunication with platforms such as Twitter trying to direct people towards official information sources and the Government now hosting a daily press briefing.

Robert questioned how we handle controversial advice and that scientific experts are unlikely to reach consensus with the final say being from political actors. Repeatedly, we have heard Boris Johnson and other political actors saying that the decisions are being driven by the science. An important point to make here, which was raised by Professor David Spiegelhalter in the Centre for Science and Policy’s (CSaP) ‘Science, Policy & Pandemics’ Podcast (Episode 2: Communicating Evidence and Uncertainty), is that SAGE is not the decision-maker, they are providing the evidence to inform decisions made by politicians. After calls for transparency, SAGE released the evidence which is guiding decisions and identified the core expert groups who they are consulting. As far as we are aware, this has not happened in such a short time frame for other events that SAGE have provided advice for, but perhaps this is because it is something that is affecting us all rather than a specific geographic location.

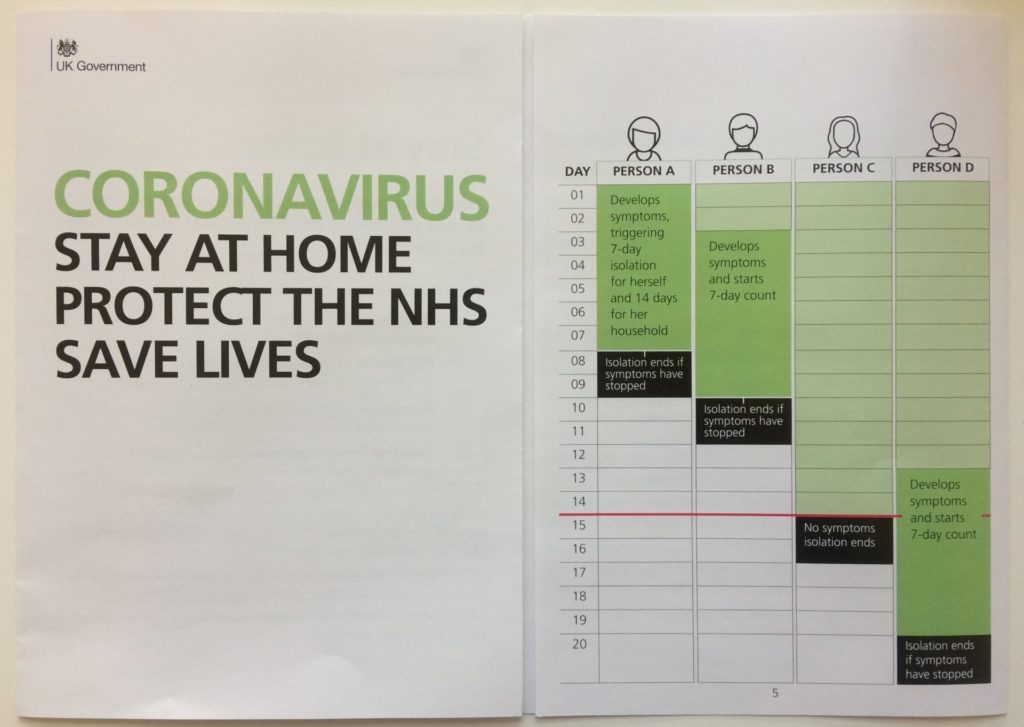

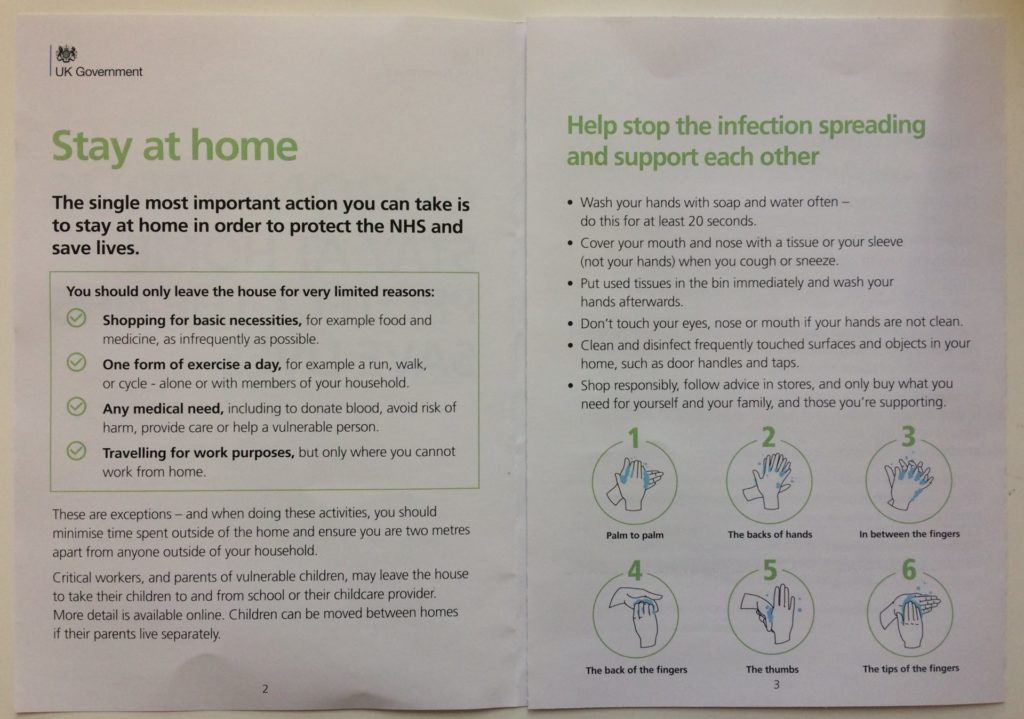

One point in Thea’s presentation that stands out is that information/evidence sometimes needs to be simplified for people to understand and act upon. I would be surprised if people in the UK had not now heard the line ‘Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives’, which is also on the front page of a booklet circulated nationwide summarising the action that needs to be taken by individuals and includes illustrations on the correct way to wash hands (see figure below).

Over the past few weeks Evidence Aid has been preparing collections of relevant evidence for COVID-19. Their aim has been to provide the best available evidence to help with the response, supporting Ben’s proposal that there needs to be research-evidence based decision-making in disaster response situations.

There is clearly a lot of uncertainty about COVID-19 and as the situation is changing day by day, it is impossible to comment on what the right or wrong approach is, and this approach has differed from country to country. One of the aims of our project is to now establish what evidence and type of experts different countries have relied upon and why the interventions have differed.

Members of the EuP team have also started a blog with opinion pieces about the pandemic including: ‘Are the experts responsible for bad disaster response?‘ and ‘Reading Elizabeth Anderson in the time of COVID-19’.

Text by Hannah Baker (published 23/04/2020)

Photographs within text by Hannah Baker, Cléo Chassonnery-Zaïgouche & Judith Weik

Thumbnail image by JohannHelgason/Shutterstock.com