January 18, 2019 at 10 a.m.

Robertson Gymnasium 1000A

The public expression of anger and even hate that we witness in our time—stirred up on social media and at campaign rallies, and provoked by growing inequality in income and opportunity—raises anew an old question about the role of emotion in political life (as opposed to, say, ideals or material interests).

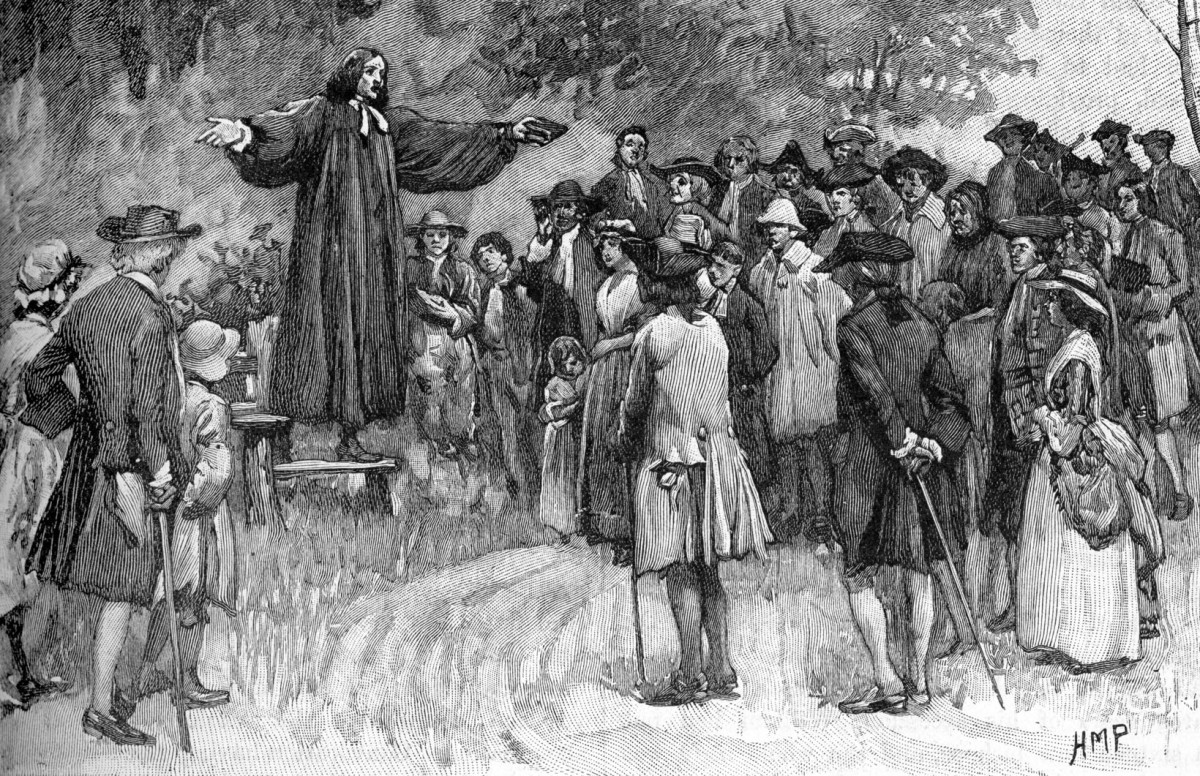

Before turning to technology or populism to explain this abrupt intrusion of the passions into politics, we might do well to consider the historic role of emotion in constituting political life. The conceptual bases of government may have originated in the rationalism of the Enlightenment, but the robust character of public life in America was shaped by a sequence of religious revivals in the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries.

The revival is derived from an element of Puritan political theology uniquely forged in seventeenth-century New England, and at the same time it marks, as the great historian Perry Miller observed many years ago, a break with that political theology by inaugurating a new kind of publicity. It names an arousal of the passions, often through the use of language, and targeted at the imagination, that creates the conditions for the ethical formation of a new moral order. Despite its origin in the theology of original sin, the revival was as much an aesthetic phenomenon as it was religious; and in the nineteenth century, it became allied to the unfurling horizon of technological progress and to the romantic emphasis on feeling over intellect.

In this seminar, we will examine the first revival, in Northampton in 1734, as it was described by Jonathan Edwards in an essay entitled, “A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls.” Our discussion of the text will be framed by Miller’s historiography, which sought to trace the intellectual legacy of Puritanism in the formation of the American character (the hermeneutics of the physical universe, a distinctive style of writing, and the voluntarism of private initiative); and which saw in the “hysterical agonies of the Great Awakening” the seeds of modern America.

Reading

Jonathan Edwards, “A Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton, and the Neighbouring Towns and Villages of the County of Hamsphire, in the Province of the Massachusetts-Bay in New-England,” in The Works of Jonathan Edwards Volume 4: The Great Awakening, (New Haven, 1972 [1736]), 130-211.

Recommended

Jonathan Edwards, “A Divine and Supernatural Light” (1734).