Mindful of AI: Language, Technology and Mental Health

Virtual Event – 01 & 02 October 2020

Workshop overview

Convenors

Bill Byrne (University of Cambridge), Shauna Concannon (University of Cambridge), Ann Copestake (University of Cambridge), Ian Roberts (University of Cambridge), Marcus Tomalin (University of Cambridge), Stefanie Ullmann (University of Cambridge)

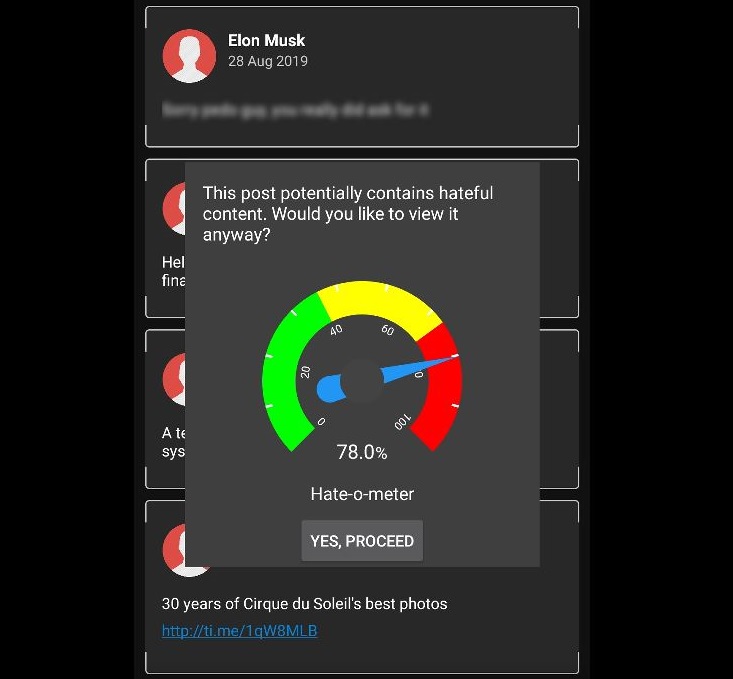

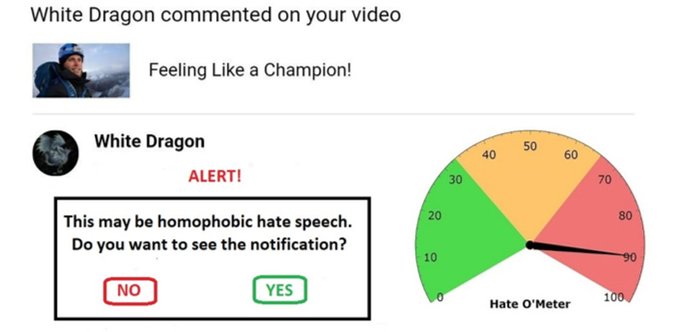

Language-based Artificial Intelligence (AI) is having an ever greater impact on how we communicate and interact. Whether overtly or covertly, such systems are essential components in smartphones, social media sites, streaming platforms, virtual personal assistants, and smart speakers. Long before the worldwide Covid-19 lockdowns, these devices and services were already affecting not only our daily routines and behaviours, but also our ways of thinking, our emotional well-being and our mental health.Social media sites create new opportunities for peer-group pressure, which can heighten feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness (especially in young people); malicious twitterbots can influence our emotional responses to important events; and online hate speech and cyberbullying can cause victims to have suicidal thoughts.

Consequently, there are frequent calls for stricter regulation of these technologies, and there are growing concerns about the ethical appropriateness of allowing companies to inculcate addictive behaviours to increase profitability. Infinite scrolls and ‘Someone is typing a comment’ indicators in messaging apps keep us watching and waiting, and we repeatedly return to check the number of ‘likes’ our posts have received. The underlying software has often been purposefully crafted to trigger biochemical responses in our brains (eg the release of serotonin and/or dopamine), and these neurotransmitters strongly influence our reward-related cognition. The powerful psychological impact of such technologies is not always a positive one. Indeed, it sometimes seems appropriate that those who interact with these technologies, and those who inject drugs, are all called ‘users’.

However, while AI-based communications technologies undoubtedly have the potential to harm our mental health, they can also offer forms of psychological support. Machine Learning systems can measure the physical and mental well-being of users by evaluating their language use in social media posts, and a variety of empathetic therapy, care, and mental health chatbots, apps, and conversational agents are already widely available. These applications demonstrate some of the ways in which well-designed language-based AI technologies can offer significant psychological and practical support to especially vulnerable social groups. Indeed, medical professionals have started to consider the possibility that the future of mental healthcare will inevitably be digital, at least in part. Yet, despite their potential benefits, developments such as these raise a number of non-trivial regulatory and ethical concerns.

This two-day virtual interdisciplinary workshop brings together a diverse group of researchers from academia, industry and government, with specialisms in many different disciplines, to discuss the different effects, both positive and negative, that AI-based communications technologies are currently having, and will have, on mental health and well-being.

Speakers & Structure of Event:

Thursday 1 October

Session 1: Social Media and Mental Health

Speakers: Michelle O’Reilly (University of Leicester), Amy Orben (University of Cambridge)

Session 2: AI and Suicide Risk Detection

Speakers: Glen Coppersmith (Qntfy), Eileen Bendig (Ulm University)

Friday 2 October

Session 3: From Understanding to Automating Therapeutic Dialogues

Speakers: Raymond Bond (University of Ulster), Rose McCabe (City, University of London)

Session 4: The Future of Digital Mental Healthcare

Speakers: Valentin Tablan (IESO Digital Health), Maria Liakata (Queen Mary University of London)

Registration

The workshop comprises four sessions. You can register for more than one workshop session. Please register for each of the four sessions if you wish to attend the entire workshop. Follow the links below to register for the individual sessions on Eventbrite:

Session 1: Social Media and Mental Health

Session 2: AI and Suicide Risk Detection

Session 3: Automating Therapeutic Dialogues

Session 4: The Future of Digital Mental Healthcare

Queries: Una Yeung (uy202@cam.ac.uk)

Image by GaudiLab/Shutterstock.com

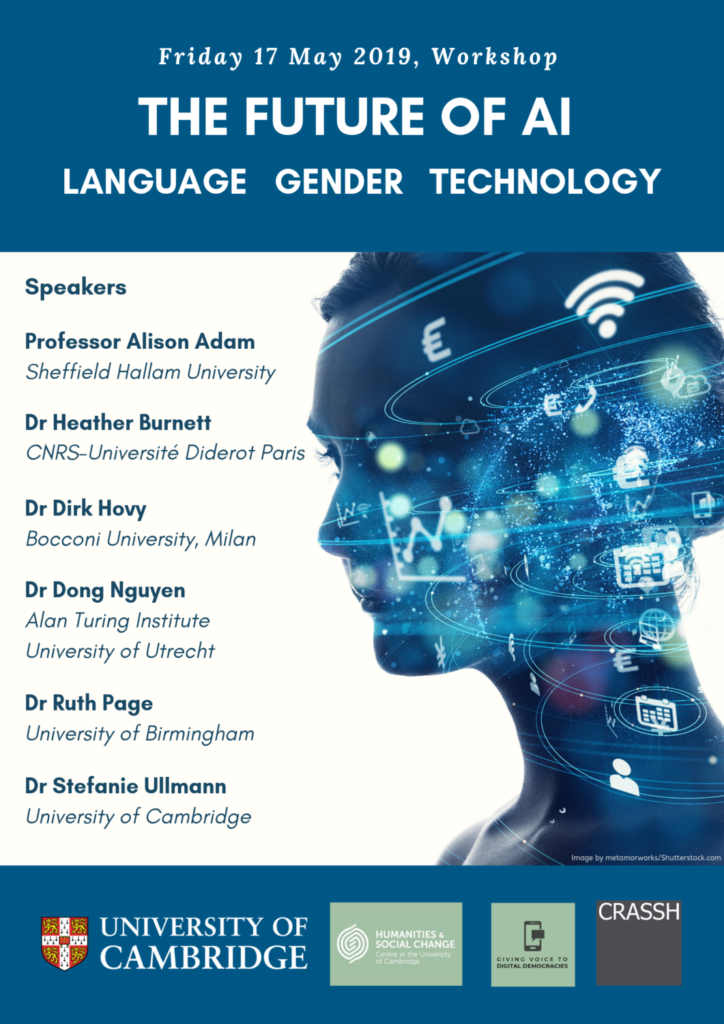

This workshop, the third in a series on the future of artificial intelligence, will focus on the impact of artificial intelligence on society, specifically on language-based technologies at the intersection of AI and ICT (henceforth ‘Artificially Intelligent Communications Technologies’ or ‘AICT’) – namely, speech technology, natural language processing, smart telecommunications and social media. The social impact of these technologies is already becoming apparent. Intelligent conversational agents such as Siri (Apple), Cortana (Microsoft) and Alexa (Amazon) are already widely used, and, in the next 5 to 10 years, a new generation of Virtual Personal Assistants (VPAs) will emerge that will increasingly influence all aspects of our lives, from relatively mundane tasks (e.g. turning the heating on and off) to highly significant activities (e.g. influencing how we vote in national elections). Crucially, our interactions with these devices will be predominantly language-based.

This workshop, the third in a series on the future of artificial intelligence, will focus on the impact of artificial intelligence on society, specifically on language-based technologies at the intersection of AI and ICT (henceforth ‘Artificially Intelligent Communications Technologies’ or ‘AICT’) – namely, speech technology, natural language processing, smart telecommunications and social media. The social impact of these technologies is already becoming apparent. Intelligent conversational agents such as Siri (Apple), Cortana (Microsoft) and Alexa (Amazon) are already widely used, and, in the next 5 to 10 years, a new generation of Virtual Personal Assistants (VPAs) will emerge that will increasingly influence all aspects of our lives, from relatively mundane tasks (e.g. turning the heating on and off) to highly significant activities (e.g. influencing how we vote in national elections). Crucially, our interactions with these devices will be predominantly language-based.