Economists in the City #5

Urban Agglomeration, City Size and Productivity: Are Bigger, More Dense Cities Necessarily More Productive?

by Ron Martin

Economists and Cities

Over the past three to four decades, economists’ interest in cities has undergone an unprecedented expansion. The renaissance of urban economics (hence the moniker ‘new urban economics’) and the rise of the ‘so-called ‘new economic geography’ (inspired especially by Paul Krugman), have together directed considerable theoretical and empirical attention to cities, how they function as economies and their importance as sources of economic growth and prosperity. This heightened focus on cities no doubt reflects the fact that, globally, the majority of people now live in cities, and that it is in cities that the bulk of economic activity is located, jobs are concentrated, and wealth is produced. And as the urbanist Jane Jacobs emphasised nearly forty years ago, cities are the main nodes in national and global trade networks.[1] Such is now the economic significance and success of cities that the leading urban economist Ed Glaeser has been moved to declare the ‘triumph of the city’, as the ‘invention that makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier’.[2]

Whilst geographers have long studied cities, not just as economic entities but also as arenas of social and cultural life, it has been the work of these urban and spatial economists that has attracted the attention of policymakers, in large part, one suspects, because of the seeming formal rigour of the models that many of these economists have used to guide and underpin their analyses of cities, and their deployment of those models to derive policy implications. The equilibrist nature of many of these models – whereby the concentration of economic activity into cities is an equilibrium outcome of market-driven economic processes – also probably appeals to policy-makers, since policies can then be justified if they work to assist the operation of those market processes and help to overcome any ‘market failures’.

The Mantra of Agglomeration

If there is one aspect of this body of economists’ work on cities that has become a dominant theme, it is that of agglomeration. Indeed, the notion has assumed almost hegemonic status in the new urban economics, the new economic geography and other related branches of spatial economics, in that the agglomeration of firms and skilled workers in cities is assumed to be the driver of various positive externalities and increasing returns effects (such as knowledge spillovers, local supply chains, specialised intermediaries, and pools of skilled labour) that in turn are claimed to be instrumental in fostering innovation, productivity, creativity, and enterprise. Further, according to this chain of reasoning, other things being equal, the larger a city is, or the greater is the density of activity and population in a city, the more powerful and pervasive are the associated agglomeration externalities: bigger is better, and denser is better.

Policymakers have eagerly seized on this sort of argument. Almost every policy statement and strategy for boosting local and regional economic performance – whether emanating from central UK Government policymakers, from the local and city policy community or from the policy reports prepared by ‘think tanks’ and consultancies – sooner or later singles out boosting ‘agglomeration’ as a key imperative. It has almost reached the point where the agglomeration argument has become unassailable, a conventional wisdom that is all but taken for granted, and unquestioned. Voices of dissent are either ignored or dismissed (typically for not being based on the sort of formal models used by the exponents of the agglomeration thesis). In many respects, agglomeration theory has become protected by ‘confirmation bias’, where empirical support (often selective) is exaggerated and evidence that runs counter to or which fails to confirm the theory is discounted.[3]

City Size and Productivity

One of the issues that illustrates this state of affairs is the claim that city size (and hence greater agglomeration) promotes higher productivity.[4] This is a particularly pertinent claim with respect to economic debates in the UK because of the current policy concern over the stagnation of national productivity, in general, and the low productivity of many of the country’s northern cities, more specifically.

A number of studies of the advanced economies – the UK included – have been conducted to estimate how productivity increases with city size, typically involving cross-section models that regress the former on the latter (with or without controlling variables). The size of the effect of city size on city productivity from these studies is, however, modest to say the least. Typically, a doubling of city size is estimated to be associated with an increase in the level of productivity of between 2-5 percent (see, for example, Ahrend et al, 2014; OECD, 2020[5]). To put these sorts of estimates into the UK context, compare, for example, London and Manchester. In 2016, London’s nominal labour productivity (as measured by GVA per employed worker) of £57,000 was 50 percent higher than Manchester’s £38,000. So, if we assume an elasticity of 5 percent, a doubling of Manchester’s population (or employment) – even if that was achievable and desirable – would only raise Manchester’s productivity to around £40,000. This hardly represents a major ‘levelling up’ towards the level of London, the aim of current Government policy.

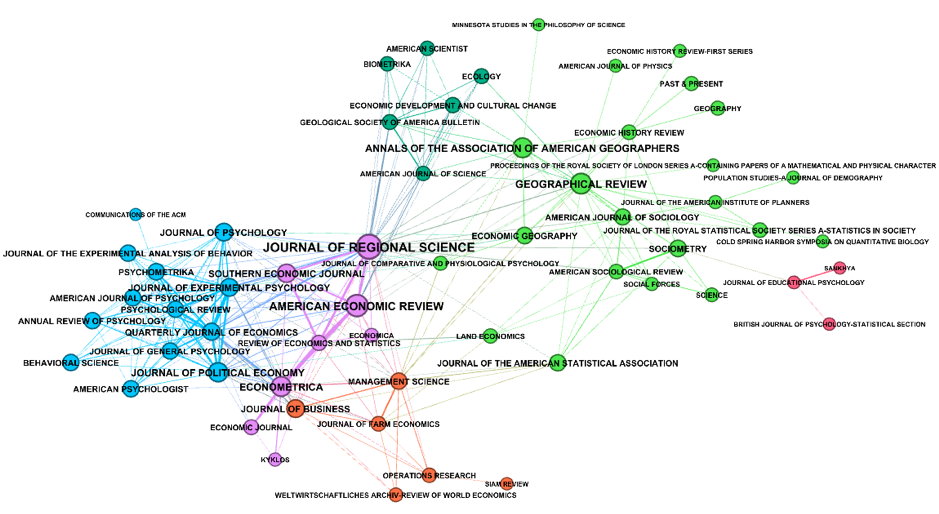

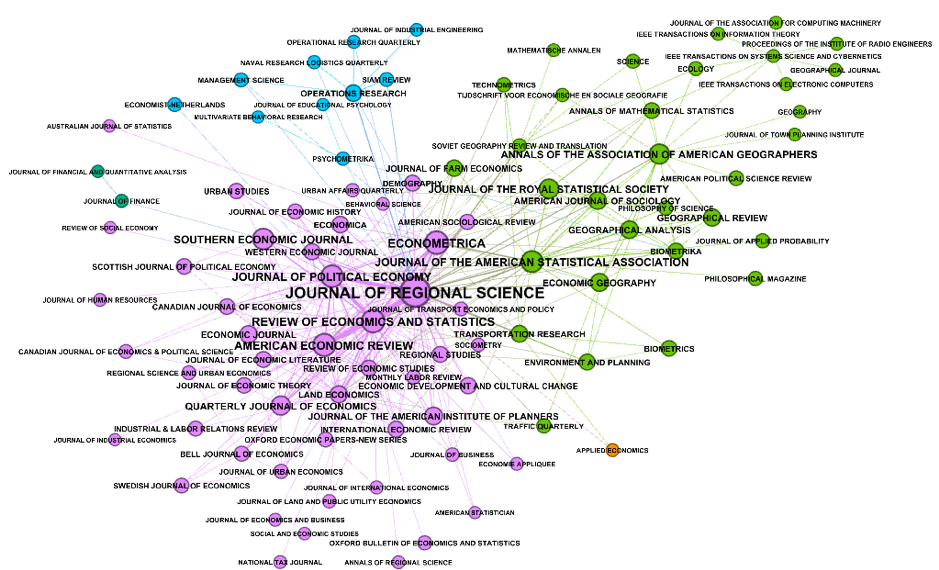

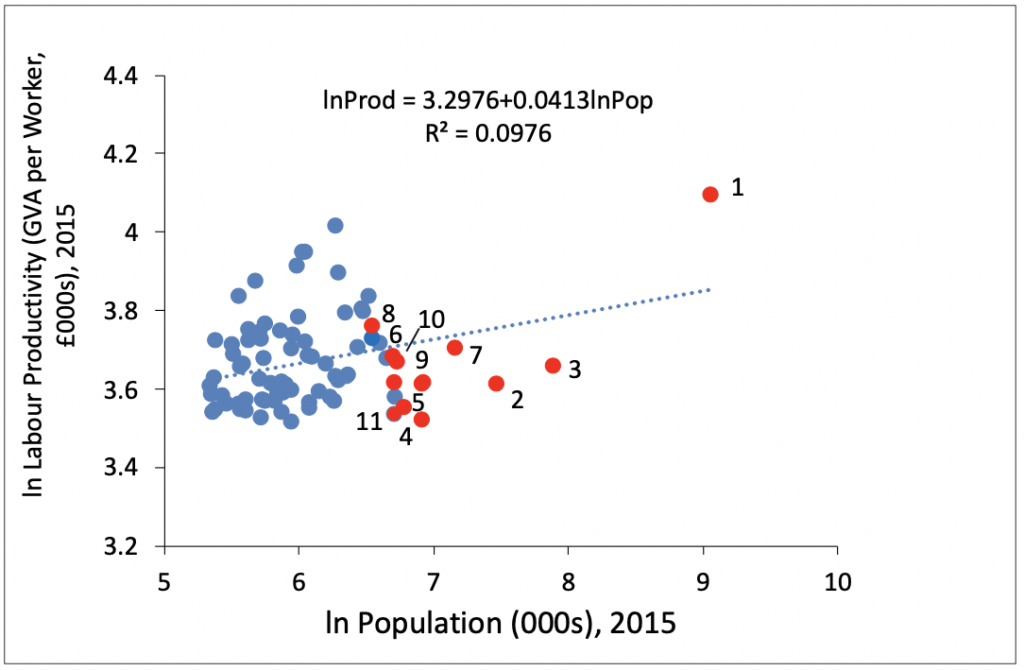

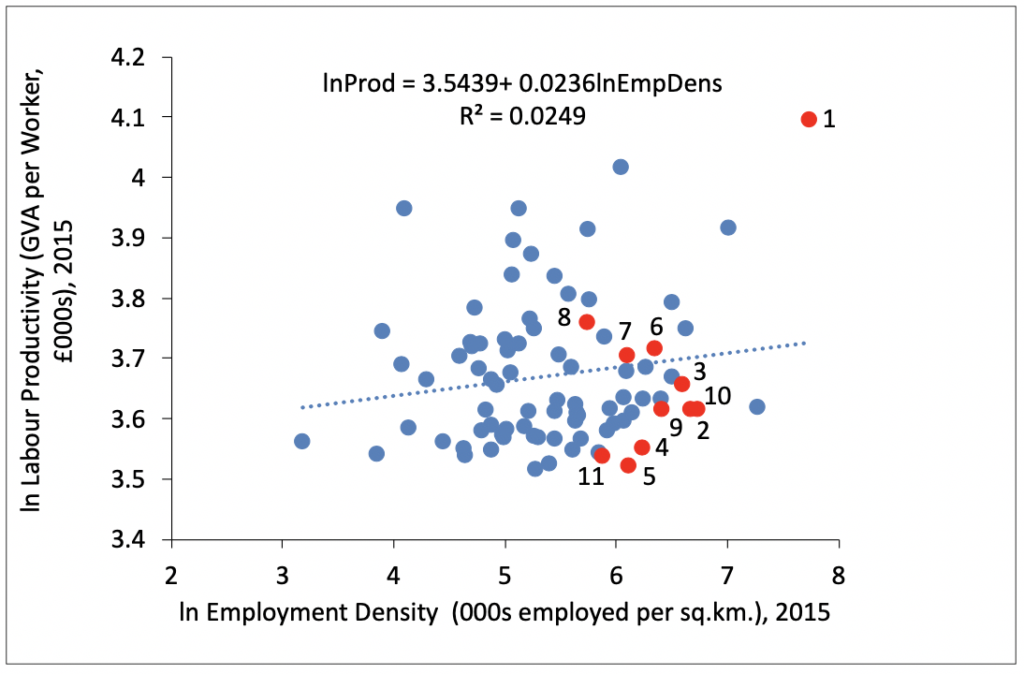

In fact, the evidence for the UK suggests that the city size argument should be viewed with caution. Using the estimates of labour productivity for some 85 British cities defined in terms of travel to work areas, the (logged regression) relationship between labour productivity (GVA per employed worker) and city size is small (a doubling of city size is associated with a mere 4 percent higher productivity (Figure1).[6] London, as the largest and most dense city, has the highest labour productivity. However, the next largest cities – Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Sheffield, Newcastle, Edinburgh, Bristol and Nottingham – all have much lower productivity, in fact below the national average. Some of the highest productivity cities after London – such as Reading, Milton Keynes, Swindon and Oxford – are all much smaller in size or less dense as urban centres. If we measure agglomeration in terms of the density of employment, as many economists would argue, the association is even smaller ( a doubling of density yields only a 2.5 percent increase in city productivity – Figure 2). Clearly, other factors than size or agglomeration alone are at work in influencing a city’s labour productivity.[7]

What Makes London So Different?

Nevertheless, the agglomeration argument has proved tenacious. Both academic economists and many policymakers have argued that the productivity gap between London and major northern UK cities is not that London is exceptional but that major northern cities are too small. Advocates of this view have invoked Zipf’s law of city sizes, sometimes known as the rank-size rule. This rule states that the population of a city is inversely proportional to its rank. If the rule held exactly, then the second largest city in a country would have half the population of the biggest city; the third largest city would have one third the population, and so on. Put another way, according to Zifp’s law, if we plot the ranks of a country’s cities against their sizes on a graph, using logarithmic scales, then the line relating rank to population is downward sloping, with a slope of -1. Appealing to this law, Overman and Rice (2008), for example, argue that while medium sized cities in England are, roughly speaking, about the size that Zipf’s law would predict given the size of London, the largest city, the major second-tier cities in the north of the country all lie below the Zipf line and hence are smaller than would be predicted.[8] This is assumed to mean that they lack the agglomeration effects that London enjoys.

The empirical evidence for Zipf’s Law is, however, highly varied internationally (see Brakman, Garretsen and van Marrewijk, 2019).[9] Further, there is no generally accepted theoretical economic explanation of Zipf’s law, nor does the ‘law’ tell us how far a city can fall below the rank-size rule line before it is deemed to be ‘too small’, or how this will affect its economic performance. Perhaps more seriously, it is indeed the case that Zipf’s law does not in fact hold for a national urban political economic system of the sort that characterises the UK.

As Paul Krugman (1996) argues, while the Zipf relationship holds fairly closely for the cities of the United States, and has done so over a long period of time, indicating a pattern of equal proportionate growth across the urban system, this is not necessarily the case elsewhere:

Zipf’s law is not quite as neat in other countries as it is in the United States, but it still seems to hold in most places, if you make one modification: many countries, for example, France and the United Kingdom, have a single ‘primate city’ that is much larger than a line drawn through the distribution of other cities would lead you to expect. These primate cities are typically political capitals: it is easy to imagine that they are essentially different creatures from the rest of the urban system. (Krugman, p. 41, emphases added).[10]

London is indeed a ‘different creature’ from the rest of the UK’s urban system. Not only is it the national capital, but a major global centre, and its development is likely to reflect the benefits of that role, and be less linked to (even significantly decoupled from) the rest of its national urban system.[11] These observations suggest that in such cases, it makes little real economic sense to argue that second tier cities below the primate capital city are ‘too small’ relative to what the rank-size rule would predict, since the size of the capital itself has to do with national political and administrative roles and factors in addition to the purely economic.

As the nation’s capital, London has long benefited from being the political centre (one the most centralised of the advanced economies), containing the nation’s main financial institutions an markets (that historically were much more regionally distributed), the main organs of Government policy-making (the UK is one of the most centralised on the OECD countries), a large number of headquarters of major corporations, the largest concentration of top universities, and a high degree of policy autonomy relative to other UK cities. This has meant that it attracts much of the talent and skilled of the country’s workforce.[12] In recent years, it has also benefited from a disproportionate share of major infrastructural investment. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that it has a high productivity. Yet the high productivity of several much smaller cities suggests that size and agglomeration are not everything.

Beyond the Agglomeration Credo

This is not to say that agglomeration is irrelevant – clearly all cities of whatever size benefit to a greater or lesser extent from the local concentration and proximity of workers, firms and infrastructures. But aiming to improve the productivity of Britain’s northern cities by substantially expanding their size or density may be neither necessary nor sufficient as a strategy. The relevant question to pose is why are smaller, and less dense, cities more productive, and what policy lessons might be learned from their experience? What a city does is obviously important, not just in sectoral terms, but also in terms of functions and tasks (and hence roles in domestic and international supply networks and chains). So, relatedly, is its export base. Further, and crucially, its innovative capacity; its ability to produce and retain, highly educated and skilled workers; its levels of entrepreneurship; the quality and efficiency of its infrastructures; and the extent of its decentralised powers of economic governance; these are all of key importance. Cities outside London have for decades scored poorly on such factors. But these drivers of productivity cannot simply or solely be reduced to ‘insufficient agglomeration’. The ‘Northern Powerhouse’ cities traditionally once formed polycentric regional systems of innovative and competitive, export-orientated manufacturing. They have lost that role through sustained deindustrialisation, in part because of globalisation and technological lock-in, in part because of spatial biases in national economic policy and management that favoured London and ignored manufacturing. Finding a new role for Britain’s northern cities will be key to their economic renaissance. Cities do not have to be big or more dense to succeed, but adaptive, dynamic and with appropriate powers of self-determination.[13] Theorising and understanding economic adaptability might yield greater policy dividends than yet more theorising and promotion of agglomeration.

[1] Jane Jacobs (1985) Cities and the Wealth of Nations: Principles of Economic Life, New York: Vintage Books.

[2] Ed Glaeser (2011) The Triumph of the City: How or Greatest Invention Makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier, London: Macmillan.

[3] The negative effects of increasing size and density – such the diseconomies of increased congestion, pollution, travel time, and land and housing costs, are infrequently given the due empirical attention they deserve. It is also significant that in surveys of quality of life satisfaction, large cities often score less well than smaller cities and towns. London reports some of the lowest average life satisfaction in the UK (see, for example).

[4] See, for example, Glaeser, E. (2010) Agglomeration Economics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Glaeser, E. (2011) The Wealth of Cities: Agglomeration Economies and Spatial Equilibrium in the United States, NBER Working Paper 14806; Combes, P., Duranton, G., Gobillon, L., Puga, D., & Roux, S. (2012). The Productivity Advantages of Large Cities: Distinguishing From Firm Selection, Econometrica, 80, pp. 2543-2594. Ahrend et al (2017) The Role of Urban Agglomerations for Economic and Productivity Growth, International Productivity Monitor, 32, pp. 161-179.

[5] Ahrend, R., et al. (2014) What Makes Cities More Productive? Evidence on the Role of Urban Governance from Five OECD Countries, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2014/05, OECD Publishing, Paris. OECD (2020) The Spatial Dimension of Productivity: Connecting the Dots across Industries, Firms and Places, OECD Regional Development Working Papers 2020/1, Paris: OECD.

[6] For a comprehensive study of the productivity performance of British cities over the past half century, see Martin, R., Gardiner, B., Evenhuis, E., Sunley,P. and Tyler, P. (2018) The City Dimension of the Productivity Puzzle, Journal of Economic Geography, 18, pp. 539-570.

[7] Nor does the spatial agglomeration or clustering of individual firms in the same or related industries necessarily increase their productivity, another conventional wisdom in the business and economics literatures (see Harris, R. Sunley, P., Evenhuis, E., Martin,, R. and Pike, A.(2019)Does Spatial Proximity Raise Firm Productivity? Evidence from British Manufacturing, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12, pp. 467-487

[8] Overman, H., and P. Rice. 2008. Resurgent cities and regional economic performance. SERC Policy Paper 1, London School of Economics.

[9] Brakman, S., Garretsen, H. and Marrewijk, C. (2019) An Introduction to Geographical and Urban and Economics: A Spiky World, Cambridge: CUP.

[10] P. Krugman (2006) The Self-organising Economy, Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

[11] For an interesting analysis of how decoupled London has become from the rest of the UK economy, see Deutsche Bank (2013) London and the UK economy: In for a penny, in for a pound? Special Report, Deutsche Bank Markets Research, London.

[12] As Vince Cable, when Secretary of State for Business in the Coalition Government of 2010, put it: “One of the big problems that we have at the moment… is that London is becoming a kind of giant suction machine, draining the life out of the rest of the country.” (Cable, V. 2013, London draining life out of rest of country). Cable was in fact merely echoing a similar view expressed 75 years earlier by the famous Barlow Commission report on rebalancing Britain’s economy: “The contribution in one area of such a large proportion of the national population as is contained in Greater London, and the attraction to the Metropolis of the best industrial, financial, commercial and general ability, represents a serious drain on the rest of the country” (Barlow Commission, 1940, Royal Commission on the Distribution of the Industrial Population. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

[13] Martin, R. L. and Gardiner, B. (2017) Reviving the ‘Northern Powerhouse’ and Spatially Rebalancing the British Economy: The Scale of the Challenge, in Berry, C. and Giovannini, A. (Eds) Developing England’s North: The Political Economy of the Northern Powerhouse, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23-58.

Ron Martin is Professor of Economic Geography at the University of Cambridge.

Other posts from the blogged conference:

The Institutionalization of Regional Science In the Shadow of Economics by Anthony Rebours

Cities and Space: Towards a History of ‘Urban Economics’, by Beatrice Cherrier & Anthony Rebours

Economists in the City: Reconsidering the History of Urban Policy Expertise: An Introduction, by Mike Kenny & Cléo Chassonnery-Zaïgouche